How offshoring paved the way for vertical integration abroad

Understanding vertical integration through the global value chain lens

Over the past few years, more and more people have begun to write about the resurgence of vertical integration as viable corporate strategy, pointing to cases like BYD, Tesla, even Ford. I too, just a few weeks back, wrote about this very subject. What’s often missing from these discussions is a closer look at why firms across different contexts of development pursue vertical integration in the first place. BYD and Tesla, for instance, may both be vertically integrated firms, but coming from different developmental contexts, the impetus behind their strategies is entirely different.

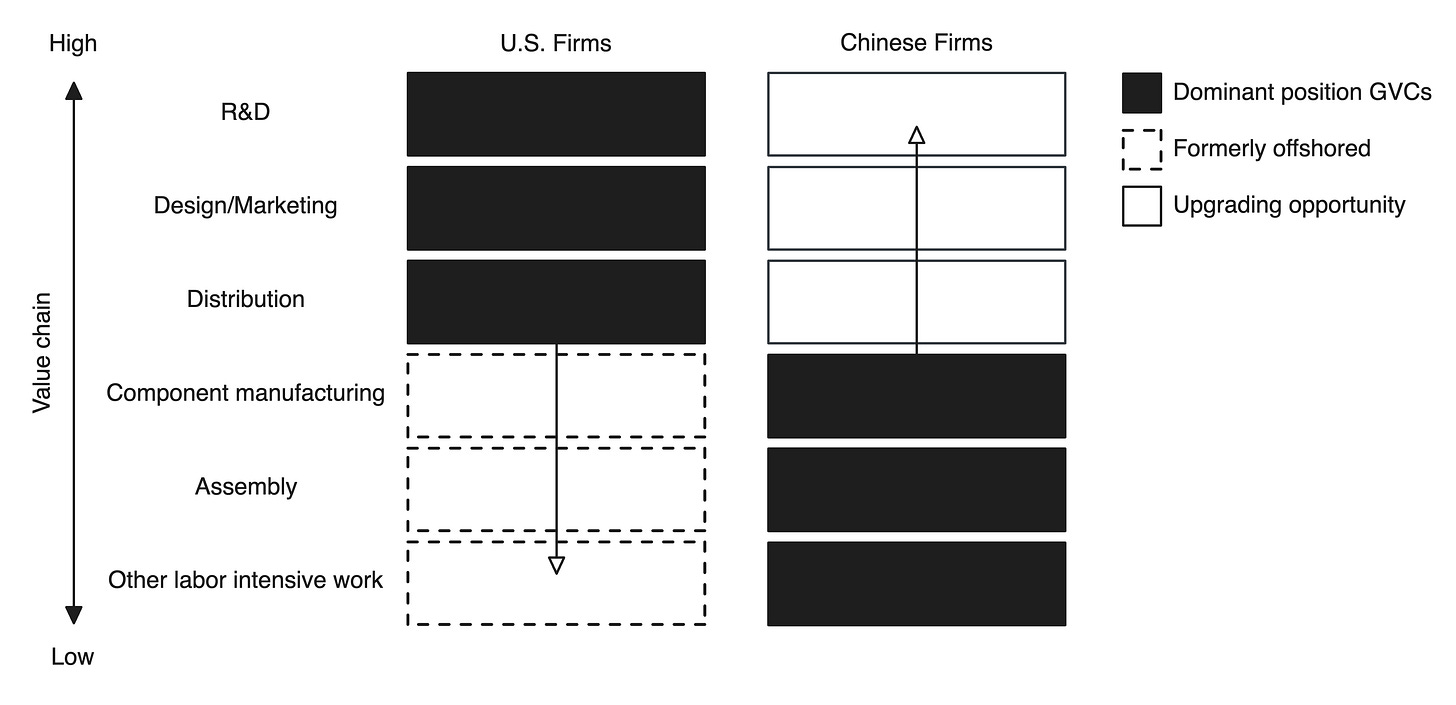

In advanced countries, vertical integration is something that firms are returning to. In the west, it is considered novel because it signals a retreat from globalization and the pattern of offshoring that has dominated corporate strategies since the 1980s. Today, there are many reasons for its return: concerns over the fragility of global supply networks (especially since the pandemic), geopolitical risk, and—perhaps most importantly—the need to restore domestic production capacity to revitalize broad-based growth. For firms in advanced economies, vertical integration usually means reabsorbing lower-value-added activities such as assembly and component manufacturing that were offshored to the developing world. (Or, as is the case of Tesla, it constructed an entirely new supply chain out of necessity and retained hierarchical control over each link.)

By contrast, in developing countries—specifically export-led countries that have exhibited high rates of development since the 1980s—vertical integration is not a retreat from globalization but one of its logical outcomes. To appreciate why and when vertical integration occurs in developing countries, we first need to understand the evolution of global value chains (GVCs) since the onset of globalization.

In the early years of globalization, the dominant strategy for lead firms in the west was dis-integration: break up the production process, offshore labor-intensive stages, and focus on high-value activities like product design, branding, and finance. This allowed firms to reduce costs, increase flexibility, and offload risk, while still capturing the lion’s share of value through control over intellectual property, branding, and other consumer-facing functions. Importantly, dis-integration was a cost saving strategy for such firms who would otherwise have to rely on a more costly (and often unionized) domestic labor force.

To economists, this fragmentation of production has long been attributed to the theory of comparative advantage. The argument is that, in a world of free trade and falling coordination costs (thanks to technologies like the internet and containerized shipping), countries with cheap labor should focus on labor-intensive production. And firms in advanced countries (where labor is comparatively more expensive) should offshore labor intensive activities in order to maximize the overall efficiency of the system. This theory implies a stable division of labor. Developing countries are expected to remain in low-value-added segments of GVCs—assembly, basic processing, component manufacturing—while firms in advanced economies would retain control over high-value functions like design, branding, and R&D.

In most cases, this is exactly what happened. Many countries that have entered GVCs at the bottom remain stuck in a low-level equilibrium trap. But some have steadily moved up the value chain, capturing ever more sophisticated and profitable segments of production.

To understand how this happened, we must go beyond traditional economistic explanations such as comparative advantage. As Ha-Joon Chang has argued, successful development often hinges on comparative advantage defiance.1 So rather than entering a GVC at the bottom and staying there, the key task for states of developing countries is to turn GVCs into stepping stones for industrial upgrading and economic development. This is the essence of “upgrading”: the process by which firms move from basic assembly into more complex, higher-value-added segments of the value chain.

There are many mechanisms that states can use for precisely this task. Joint ventures, forced technology transfers, investment in R&D to increase absorptive capacity, among many other mechanism have been used to help suppliers in developing countries upgrade. This is, in fact, the subject of a rich body of literature at the intersection of development studies and GVCs.

In successful cases—such as China, South Korea, and Japan—domestic suppliers have steadily acquired new capabilities, enabling them to capture larger portions of the value chain and negotiate more favorable terms with lead firms. Over time, more stages of production have become concentrated within national borders. This has led to a form of regional vertical integration, where entire supply chains are now localized into dense, interlinked ecosystems of suppliers. Today, many so-called “global” value chains are no longer truly global, but operate at a regional or even local scale, with multiple stages of production housed within a single region, city, or industrial zone.

In certain sectors, this has gone even further with vertical integration taking place at the level of the firm. This is tends to happen in sectors where knowledge is tacit or where coordination is complex. In such contexts, firms vertically integrate to reduce coordination costs and eliminate markups from intermediaries. The electric vehicle (EV) industry is a case in point. China's top EV maker, BYD, began as a battery maker (manufacturing for cellphone companies like Nokia and Motorola) and incrementally over decades captured more of the EV value chain—electric powertrain, semiconductors, transmission, cockpits, breaks, etc. And by keeping all stages of production under its control, the company has been able to keep costs down making it perhaps the most price competitive EV maker today.

A key difference in China’s development path is that—unlike earlier fast-developing economies such as Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan, which followed the lead of advanced countries by offshoring labor-intensive segments of the value chain to less developed nations—China has largely retained the entire value chain within its borders. In some cases, it has even consolidated multiple stages of production within a single firm. This has remained true even as China has successfully upgraded into higher-value-added activities. One reason it has been able to do so is its vast supply of cheap labor, which reduced the pressure to outsource lower-value-added production abroad.

What this story of vertical integration in developing contexts reveal is that vertical integration can come about for different reasons. In advanced economies, vertical integration is often about reclaiming what was lost to globalization: reabsorbing outsourced activities or building new supply chains from scratch to regain manufacturing control. In certain developing countries, by contrast, it’s about climbing upward—gaining capabilities, capturing more value, and reducing dependence on external partners.

The stylized diagram below captures this asymmetry: firms in advanced vs developing contexts must move in opposite directions to achieve vertical integration.

In this way, offshoring and vertical integration aren’t opposing strategies but mirror images of each other—each aimed at cost control, but from opposite ends of the value chain. For lead firms in the West, cost savings came from offshoring and dis-integration. For firms in developing countries like BYD, cost savings and competitiveness come from putting the chain back together again.

See Lin, Justin, and Ha‐Joon Chang. 2009. “Should Industrial Policy in Developing Countries Conform to Comparative Advantage or Defy It? A Debate Between Justin Lin and Ha‐Joon Chang.” Development Policy Review 27(5): 483–502. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00456.x.

Great overview of this issue. It's incredible to think the Western powers were ever willing to break up their supply chains, yet it was very much a product of the time. They believed they won, TINA was in place, and it seemed that global integrate markets were the norm for the future.

The return to international competition and imperial decay reminds me of the discussion of the international system Hymer made in his prescient 1972 paper "The internationalization of capital". In it, he predicts the global organizations of production that rose just a few decades later, but unlike the comparative advantage focus, he centers imperial relations of power. Also, the division between manufacturing and R&D/Design today mirror the division between so-called mental and manual labor but in the form of the state. There are states that "think" and those that merely "build".

Love the takeaway of the mirrored practice of vertical integration and offshoring. Thanks for explaining it so clearly!