From Platform Capitalism to the Cloud Business Model

New article about the political economy of the AI transition.

My article with Kathleen Thelen, “Cloud Capitalism and the AI Transition,” is now out in Politics & Society! The paper actually came out in December, so this post is a bit overdue. I’ll blame some of that on a stretch of near-constant travel for the past month—Shanghai, Guiyang, Chengdu, Shenzhen, Hong Kong—and the fact that I somehow managed to get sick twice along the way.

Of course I’m biased, but I really think that readers of Value Added, especially those academically inclined, will find the article quite useful. It’s an effort to make sense of the AI transition by starting, not from the cutting-edge language models themselves, but from its underlying political economy. It looks at the industrial structure of the AI economy, the entanglement of the cloud hyperscalers in state power (what we call in the paper the techno-nationalist alliance), and new forms of competition which we argue are quite different from the preceding era of platform capitalism.

Below, I’ll sketch a few of the paper’s main themes. I’ll resist the temptation to summarize the whole thing, but sharte just enough to motivate you to click through to the article and read it in full.

After Platform Capitalism?

The very first draft of my article began as a response to Sabeel Rahman and Kathleen Thelen’s influential 2019 paper on “The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism.” Their paper walks us through platform capitalism’s core features—its consumer-investor coalition, focus on horizontal dominance, and reliance on a precarious and increasingly gigified labor regime. It also explains why the institutional configuration of the United States was uniquely conducive to this model’s ascent.

When I read their piece, it immediately stood out as one of the most useful text for understanding the political economy of the platform era. It became my go-to recommendation to friends and colleagues who wanted to read something about platform capitalism (alongside, of course, Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism book). However, as much as I admired it, I couldn’t help but notice that my experience having worked in Microsoft’s Cloud and AI division was completely overlooked by their paper.

From this perspective, it was obvious that the most consequential developments at the time were not happening in consumer-facing apps or gigified labor platforms. Instead, they were taking place under a different business model that was organized around expensive infrastructure, long-term planning, and often much deeper dependencies between firms, customers, and even governments. In fact, the common features of platform capitalism—footlooseness, asset-light strategies, and regulatory arbitrage—didn’t match what I was seeing at all.

For some context, I read their paper when I took a class taught by Professor Thelen. And when I argued for my term paper that her platform business model paper with Sabeel completely missed the developments that now underpin the AI boom, we decided to develop the cloud business model paper together.

Our aim was not to overturn the platform capitalism framework. But we felt that the prevailing theories used to describe the knowledge economy were not sufficient for understanding how such an asset-light business could lead up the asset-heavy underbelly atop which the ChatGPT moment relied on. To make sense of this, we needed to explain another development in the knowledge economy: the rise of the cloud business model, and its central role in the AI transition.

The Cloud Business Model

The cloud business model is immensely important not only because it is the foundation on which the development of large language models was made possible but also because it is now the primary vehicle by which AI can diffuse to other sectors of the economy. So to understand the AI transition, we need to understand how the cloud differs from the platform model that came before it.

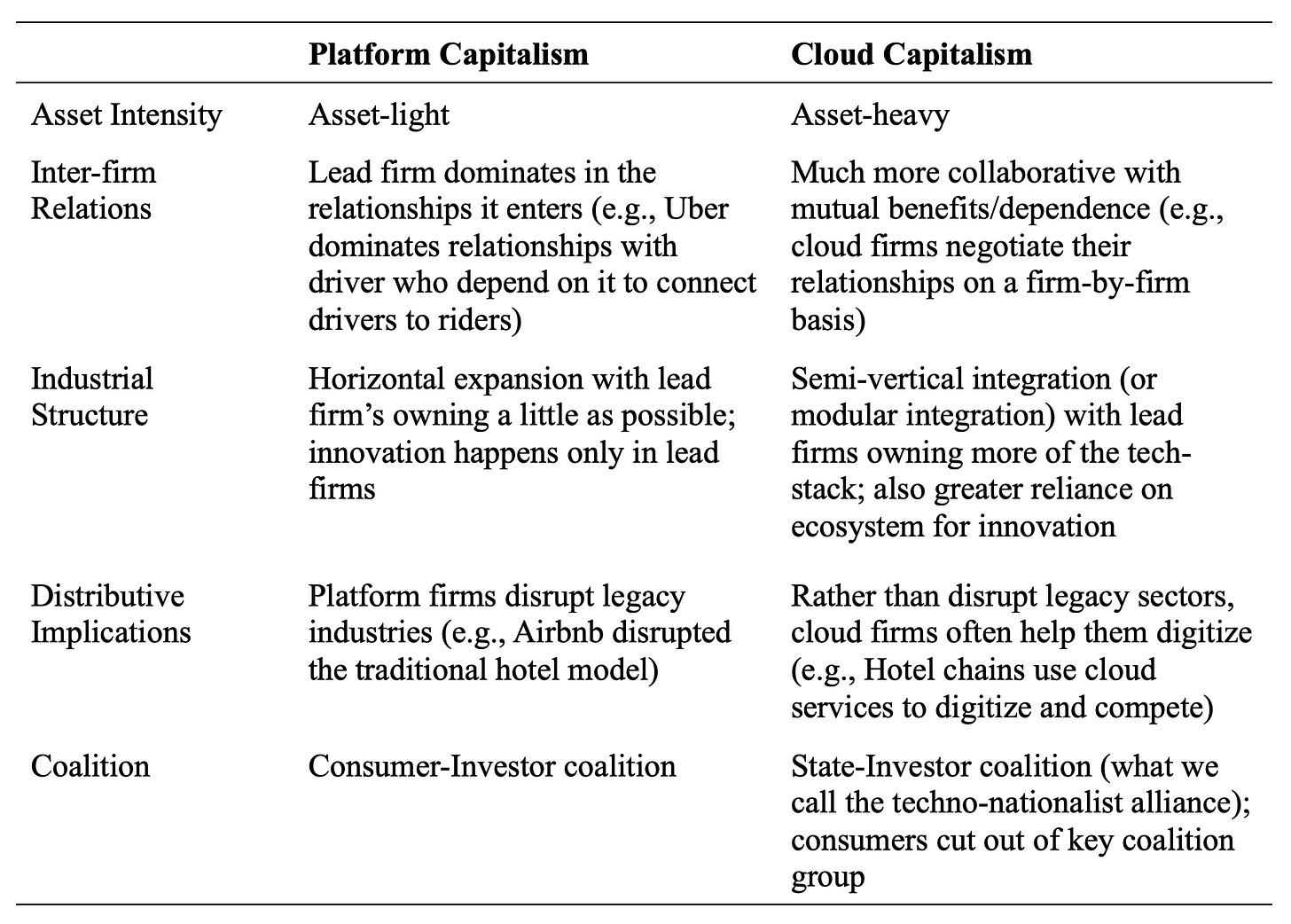

In this table, I’ve summarized some of the notable shifts. I won’t walk through each of them. The paper already does that well, so I’ll encourage you to read it directly. But one feature is worth emphasizing: the cloud’s extreme asset intensity. Unlike the largest platform firms, which are famously asset-light (Airbnb, for instance, controls all the lodging without owning it), cloud providers are investing extraordinary sums in physical infrastructure, above all in data centers. And in doing so, they have become much more vertically integrated across the stack. This, of course, is a well-known fact by now. Everyone has seen the graphs of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft’s CAPEX spending shoot up over the years.

However, this feature of the cloud business model is particularly worth highlighting because this new asset-heavy approach in what was a traditionally asset-light sector carries important political consequences. During the platform era, firms’ asset-light structure made venue arbitrage a key strategy: operations could be shifted across jurisdictions to minimize taxes, evade regulation, or exploit legal gray zones. Cloud firms, by contrast, are physically anchored. Their dependence on massive data centers, energy infrastructure, and long-term fixed investments ties them tightly to particular places—and, by extension, to the states that govern them.

As a result, the relationship between leading tech firms and the state has begun to change. Rather than treating regulation as something to be avoided, cloud providers—and especially their leaders including Sundar Pichai, Larry Ellison, Satya Nedella, and Jeff Bezos—increasingly seek accommodation and partnership with the government. This has given rise to what we call a techno-nationalist alliance: a political alignment in which the state facilitates rapid data center build-outs at home (and in allied countries), while simultaneously deploying export controls and sanctions to hobble geopolitical rivals abroad.1

This shift produces quite a different political coalition. Platform firms are anchored in a consumer–investor alliance: investors pursuing winner-take-all returns frame platforms as protectors of consumers against “crippling” regulation, casting state capacity as an obstacle to innovation and choice. The state, in this view, is something to be evaded or politically neutralized. The cloud business model points in the opposite direction. Its asset-heavy character underpins the techno-nationalist alliance described above. In this configuration, the central coalition is between the state and investors; consumers are cut out entirely.

Concluding thoughts

I hope this brief post is enough to entice you to read the piece in full. Theres much more in it on the hyperscalers’ competitive strategies, their relationships with suppliers and customers, and even labor/distributional implications. My hope is that it also offers a useful way of thinking about the AI transition: not as a story about an individual technology or the most cutting edge labs, but as a broader shift in the underlying political economy of the digital economy.

There are, of course, other forces pulling the tech elite towards Trump. In a previous post, I argued that the surge in tech worker activism beginning in 2018 helped push executives toward an explicitly anti-”woke” posture, which they saw as the root cause of internal dissent. Henry Farrell has also noted that senior figures in Silicon Valley felt personally sidelined during the Biden administration, in one case complaining that they were granted access only to “second-level” officials rather than the White House itself.

While I buy the qualitative argument that cloud capitalism is asset-heavy, to-date, empirical results don't appear to prove the point.

For example, if you compare Microsoft's asset turnover ratio to cloud revenues as a percentage of total revenues, asset turnover as of 2025 was the same as the 10-year average, while cloud revenues have increased their share of total revenue by 12 percentage points. Meanwhile, Google has increased its proportion of cloud revenues by almost 9 percentage points from 2017-2024, while actually increasing its asset turnover.

In other words, in our best examples of hyperscalers (Amazon is hard to analyze because of the large non-cloud operations), asset intensity is either flat or declining as the contribution of cloud revenues to each hyperscaler's business increases.

Definitely an interesting area for future research.