Why layoffs are the new normal in tech

A story of labor relations in America's most innovative industry.

Just last month, Microsoft announced over 6,000 job cuts—its second largest layoff ever. And they’re not alone. Since the start of the year, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Salesforce, and many other household tech names have also slashed headcount. What makes these layoffs especially striking is that they’re happening not during a downturn, but amid a surge in tech stock valuations. Microsoft’s layoffs, for instance, came in the same month that its stock price approached all-time highs.

Since 2022, layoffs have become a new normal for the tech industry with 2023 being worst layoff year in the modern tech industry. Then, layoffs were seen as a sensible correction to overzealous hiring in the preceding two years, where tech companies went on a hiring spree as they realized that the pandemic would accelerate the pace of digitization.

What’s striking now is that, two years later, the layoffs haven’t stopped, even as the tech sector surges ahead. If anything, they’ve become routine; embedded in quarterly planning cycles, not just as emergency responses. Layoffs, initially framed as a necessary correction the pandemic hiring spree, seems to have far outlived the conditions that justified it.

Today, executives are pointing at a new explanation: AI automation. They are claiming that AI is not just as a productivity booster, but a new reason to cut jobs. But we should be skeptical of this narrative. The scale and timing of recent layoffs suggest that AI may be more pretext than cause—an excuse to further cut costs without alarming investors.

This post argues that what’s unfolding is not just a reaction to macroeconomic shifts or technological change, but a deeper reconfiguration of labor relations in tech. And as longtime readers of my newsletter will know, labor relations has everything to do with innovation. But to understand how we got here, we need to go back in time to the industry’s high-flying ZIRP years to understand labor relations in this industry.

Tech's high-flying ZIRP years

For many years, tech workers had tremendous labor market power. For most of the 2010's, computer science graduates were easily making six figures right out of college. Big tech firms courted engineers, designers, and program managers with hefty compensation packages, beautiful offices, and endless perks. These companies turned their workplaces into some of the best places to work, setting a new standard for what good work looked like around the country.

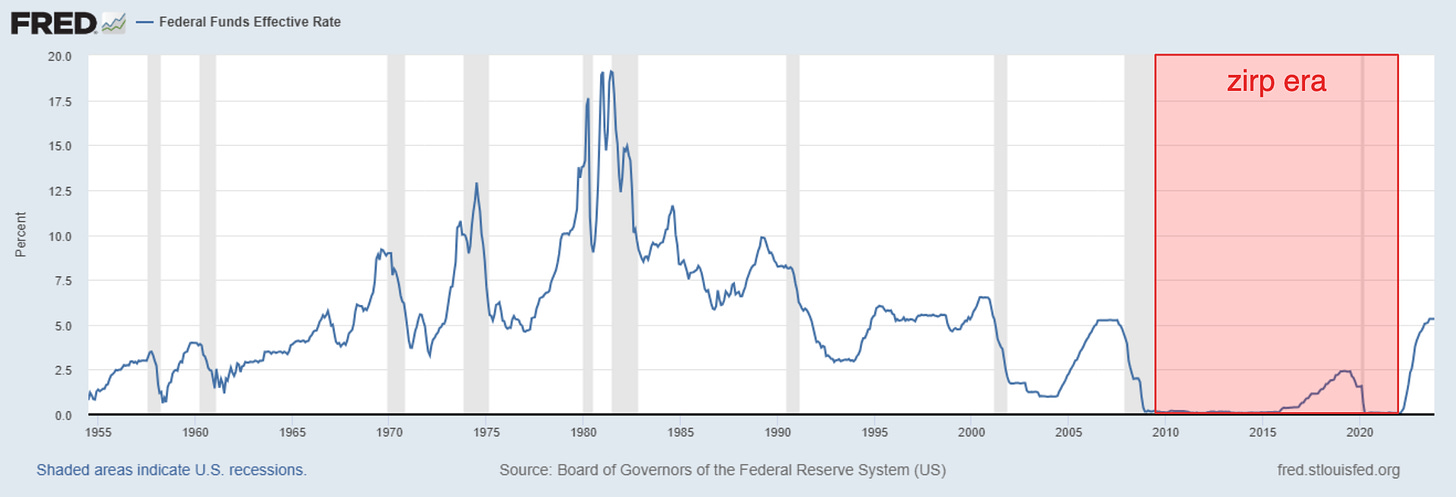

All this was underwritten by an extraordinary financial backdrop shaped by over a decade of loose monetary policy. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to near zero to stimulate the economy. And for most of the 2010s, rates remained near zero, creating what economists call an era of Zero Interest Rate Policy, or ZIRP.

During these years, when capital flowed freely into Silicon Valley, firms rapidly expanded into new digital segments, and demand for tech talent far outpaced supply. This gave workers significant leverage. Job seekers often collected multiple offers and used them to negotiate higher compensation packages. Inside companies, talent scarcity gave individual workers substantial autonomy.

All this was kicked into high gear when the pandemic supercharged the digital economy. Kitchen tables became office desks, and the digital tools that once complemented in-person work became the lifeline for businesses around the country. Already one of the most powerful forces in the U.S. economy, the tech sector suddenly became the infrastructure underpinning every aspect of life. Demand for technical skills exploded, and tech companies scrambled to snatch up engineers, designers, and data scientists as fast as they could, often without knowing what to do with them. Between 2019 and 2022, Amazon and Meta more than doubled their headcount, growing by 106 and 103 percent, respectively. Major firms like Microsoft and Alphabet each hired tens of thousands of new workers between those years; 80,000 and 60,000 respectively.

Then inflation hit. Strict pandemic protocols and intermittent shutdowns slowed production in factories around the world. The result was a series of major bottlenecks to the global supply chains. Adding fuel to fire, the Russian invasion of Ukraine sent energy prices through the roof. By 2022, inflation peaked at 9.1 percent, making it the largest 12-month increase since the early 1980s. The Federal Reserve responded to rising inflation with one of the fastest tightening campaigns in decades, raising rates from near zero to roughly 5.5 percent after ten consecutive hikes in just a 15 month timespan.

Why layoffs are the perfect cost-cutting tool

When interest rates are low, capital is cheap. Investors, gaining minimal returns from idle cash, become eager to deploy money into new ventures. And while low interest rates encourage economic expansion across all sectors, they are especially favorable to the logic underpinning the tech industry’s business model. Tech firms thrive on rapidly acquiring users and scaling their services. Their success hinges on achieving strong network effects such that the value of their platform increases as more users join it. This dynamic creates incentive for firms to operate at a loss, burning through cash to acquire users, scale their platform, and entrench their position—all in hopes of eventually dominating winner-takes-all markets.

But if one winner takes all, the rest are destined to fail. In other words, tech firms are extremely risky investments. This is why a zero-interest-rate environment is critical for tech’s expansion. For investors, it makes tech’s high failure rate acceptable. After all, when idle cash earns virtually nothing, even long-shot bets on future dominance can seem worthwhile. And so, venture capitalists are willing to underwrite a tech firm’s scaling costs, not for guaranteed returns, but for the possibility of spectacular ones.

This was the financial environment that supercharged tech’s expansion since the 2008 financial crash. But in 2022, with the onset of inflation, the industry built on cheap capital ground to a halt. In a high-interest rate environment, a high-risk, high-reward logic investment model is far less tenable. The opportunity cost of risky investments increases dramatically because cash no longer sits idle but accrues real value in safer assets. As a result, investors become more cautious, demanding safer returns and more predictable outcomes. For tech firms, this means that executives can no longer justify burning cash in the name of growth. Lavish spending on moonshot projects, generous perks, and fast growing headcount starts to look less like visionary leadership and more like fiscal irresponsibility.

For asset-light tech firms, labor is often the largest cost and the easiest to cut. During the ZIRP years, keeping an extra engineer on payroll was a small price to pay compared to the potential upside of a breakthrough they might help deliver. But in an environment of rising interest rates, every employee represented a financial trade-off. Firms had to weigh the cost of each new hire against the guaranteed return of simply holding that cash in the bank. In this context, tech workers were no longer treated as future value-creators by default but had to prove their value by generating short-term returns.

Yet unlike traditional workers, whose labor is tightly coupled with the daily revenue a firm generates, most tech employees do not generate recurring or short-term revenue but are instead tasked with building products aimed at future returns. Because of this, laying off a tech worker wouldn’t result in revenue loss since the value of their past labor has already been congealed into codebases on which digital products are built. And as a result, the absence of their labor may not be felt until much later, if at all.

This was made clear when Elon Musk, after acquiring Twitter, slashed 80 percent of the company's headcount without fundamentally undermining the stability or usability of the social media platform. So, whereas a traditional firm would see a direct reduction in revenue when cutting their workforce, layoffs in tech are an immediate cost saving (and thus a boost to profitability) without any short-term penalty.

This is precisely the mechanism that tech firms took advantage of. At the end of 2022, Meta—one of the most aggressive hirers during the ZIRP years—cut 11,000 jobs that November, amounting to over 10 percent of its workforce. Amazon followed with axing 10,000 corporate employees. By year’s end, nearly 93,000 U.S.-based tech workers had been let go, marking a historic high for the industry. Each layoff announcement triggered a bump in stock price—Meta’s first major round sent shares up 13 percent overnight. In a world designed to maximize shareholder profits, layoffs were handsomely rewarded.

Tech's addiction to layoffs

What began as a response to a deteriorating macroeconomic outlook and overzealous hiring during the Covid boom has since solidified into a lasting pattern. Trueup.io projects that nearly 200,000 tech employees will face layoffs in 2025—a figure that approaches 2022 levels. While it falls short of the staggering 400,000 layoffs recorded in 2023, it remains dramatically higher than anything seen during the ZIRP years, when tech layoffs were rare and job security was largely taken for granted.

What has become clear is that tech layoffs, initially framed as a necessary correction, has far outlived the conditions that justified it. Throughout 2023, the U.S. economy repeatedly defied expectations. Consumer spending remained strong, job growth beat forecasts month after month, and inflation gradually slowed.

By mid 2023, as inflation dropped to three percent (from nine percent in the year prior), the Federal Reserve managed a so-called "soft landing," cooling the economy without tipping it into recession. Tech giants like Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Amazon all reported stronger-than-expected earnings in the first quarter of 2023, signaling a return to profitability. Meanwhile the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT injected a new jolt of boosterism—and with it, a massive injection of new capital—into the sector. And yet, even as recession fears have subsided and earnings rebounded, tech layoffs seem now to be a permanent fixture of the sector. What gives?

Although inflation has quelled, we're still far from zero-interest rate territory (4.5 percent at the time of writing, down about one percent from one year ago), meaning that we can't expect the tech labor market to bounce back to ZIRP era highs. But two others reasons for continued tech layoffs have emerged. The first is the political backlash against DEI initiatives, led in large part by Trump's re-election. In response, nearly every major tech company has scaled back or eliminated DEI programs, slashed related funding, and deprioritized inclusion efforts. Once framed as core to company culture and innovation, DEI have been recast as luxuries in the low-interest rate environment and something that they can no longer afford. (DEI cuts, however, can only account for a relatively minor portion of layoffs.)

The second is AI. As tech executives tout the potential of AI to boost productivity and streamline operations, they are supposedly "dog fooding" these technologies (testing it first within their own firms) and framing it as a rationale for workforce reduction. AI is indeed appears to be good at coding tasks. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has even said that AI has the potential to write 90 percent of the code for big tech firms within the next year. Mark Zuckerberg also stated that AI could potentially replace entry positions up to mid-level software engineers as early at this year. Despite this hype, many engineers still say that the current capabilities of AI are nothing more than glorified search engines for them (and as a former engineer, I would largely agree). In other words, AI seems more like an excuse to continue cost-cutting rather than the driving force.

Resetting labor relations

There is another reason, one that I think is central to understanding why tech layoffs are continuing till today: the reassertion of managerial control. Over the past decade, tech workers had a unique degree of labor market power that—when combined with their techno-utopian ideology—underpinned an unprecedented wave of workplace activism. From the 2018 Google Walkout to protests against military contracts, surveillance technologies, Big Oil, and providing technology to authoritarian governments, tech workers increasingly organized not just for wages or perks, but for a say over how the technology they built was being used. Collective Action in Tech, a non-profit that documents employee activism in tech and also a group that I'm a part of, shows that over 50 instances of tech worker activism took place in 2019 alone.

To tech executives, this was a dangerous trend that needed to be squashed. As the tech industry expanded into new lines of business and grew into the monopolies that it initially sought to undermine, the old mission-driven rhetoric central to Silicon Valley’s ideology was no longer enough to keep workers aligned with management. And as tech workers took to major media outlets to attack their company's then-still pristine brands, employers began to closely monitor employee dissent, limiting internal communications to work-related discussions, and even hiring union busting consultants—in effect doing whatever they could to bring the balance of power back to their side.

Quickly, a new consensus among tech's billionaire class was being formed. Marc Andreessen, a prominent venture capitalist, railed against the previous era of employee activism, saying that "the [tech] employee base is going feral. There were cases in the [first] Trump era where multiple companies I know felt like they were hours away from full-blown violent riots on their own campuses by their own employees."

With new urgency to claw back power from an increasingly mobilized workforce, the tech slump in 2022 and the subsequent raising of interest rates came as a blessing to tech's billionaire class. These macroeconomic conditions gave tech employers an easy justification for sweeping layoffs and thus an opportunity to discipline vocal employees and regain managerial control in a sector that has long given workers their way. Return-to-office mandates and performance improvement plans (popularly known as PIPs) have also been increasingly used to reinforce a climate of compliance.

Tech's new labor relations regimes carries consequences not just for workers, but for innovation itself. The tech industry has long relied on the creativity and self-initiative of its workforce—qualities that thrive in environments of trust and autonomy. As firms double down on these austerity measures, they risk undermining the very conditions that once enabled workers to again and again generate breakthrough ideas. When workers are subject to narrowly defined KPIs, daily scrutiny, and fear of losing their job, the industry doesn’t just become less humane; it becomes less innovative. With layoffs the new normal, tech companies may ultimately be stifling the ingenuity that made them powerful to begin with.

# Why Tech Layoffs Will Revitalize Silicon Valley

The current wave of tech layoffs, despite the immediate disruption, represents a necessary correction that will ultimately benefit Silicon Valley's innovation ecosystem.

Throughout the 2010s, young engineers exhibited a troubling myopia, focusing their ambitions almost exclusively on securing positions at or orchestrating acquisitions by the major tech conglomerates. This concentration of talent created a stagnant monoculture where the industry's brightest minds gravitated toward increasingly bloated organizations rather than pursuing diverse technological challenges.

The AR/VR sector exemplifies this dysfunction perfectly. It has become an industry that systematically incinerates capital based on nothing more than utopian enthusiasm from technologists who fundamentally misunderstand human behavior. Despite Silicon Valley's fervent belief in virtual worlds, it turns out most people prefer touching grass—a reality that countless failed product launches have painfully demonstrated.

The current talent dispersion will force a healthier distribution of engineering expertise across industries that desperately need technological innovation but have been starved of top-tier talent. Finance, healthcare, manufacturing, agriculture, and countless other sectors will finally gain access to the kind of technical sophistication that has been artificially concentrated in a handful of platform companies.

Perhaps most importantly, this shift will fundamentally alter startup incentives. Rather than optimizing for acquisition by big tech—a strategy that prioritizes hype generation over product development—entrepreneurs will be compelled to focus on building solutions for actual customers with real problems. This represents a return to first principles: creating value rather than engineering favorable acquisition metrics.

The result should be a more resilient and genuinely innovative tech ecosystem, one where talent serves the broader economy rather than being hoarded by a few dominant platforms pursuing increasingly speculative ventures.

These layoffs aren’t about AI. They’re about control.

During the zero-interest years, tech workers had leverage. That scared the people up top. Now that capital costs something, the C-suite found its chance to reset the balance. Fewer perks, more obedience.

They’re calling it efficiency. But gutting teams to goose stock prices doesn’t build better products. It hollows out the companies that once led by daring, not discipline.

So what happens when the companies that used to build the future start playing defense?