A brief history of firm strategies in the auto sector

And why the EV era demands new thinking in production strategies and supply chain governance.

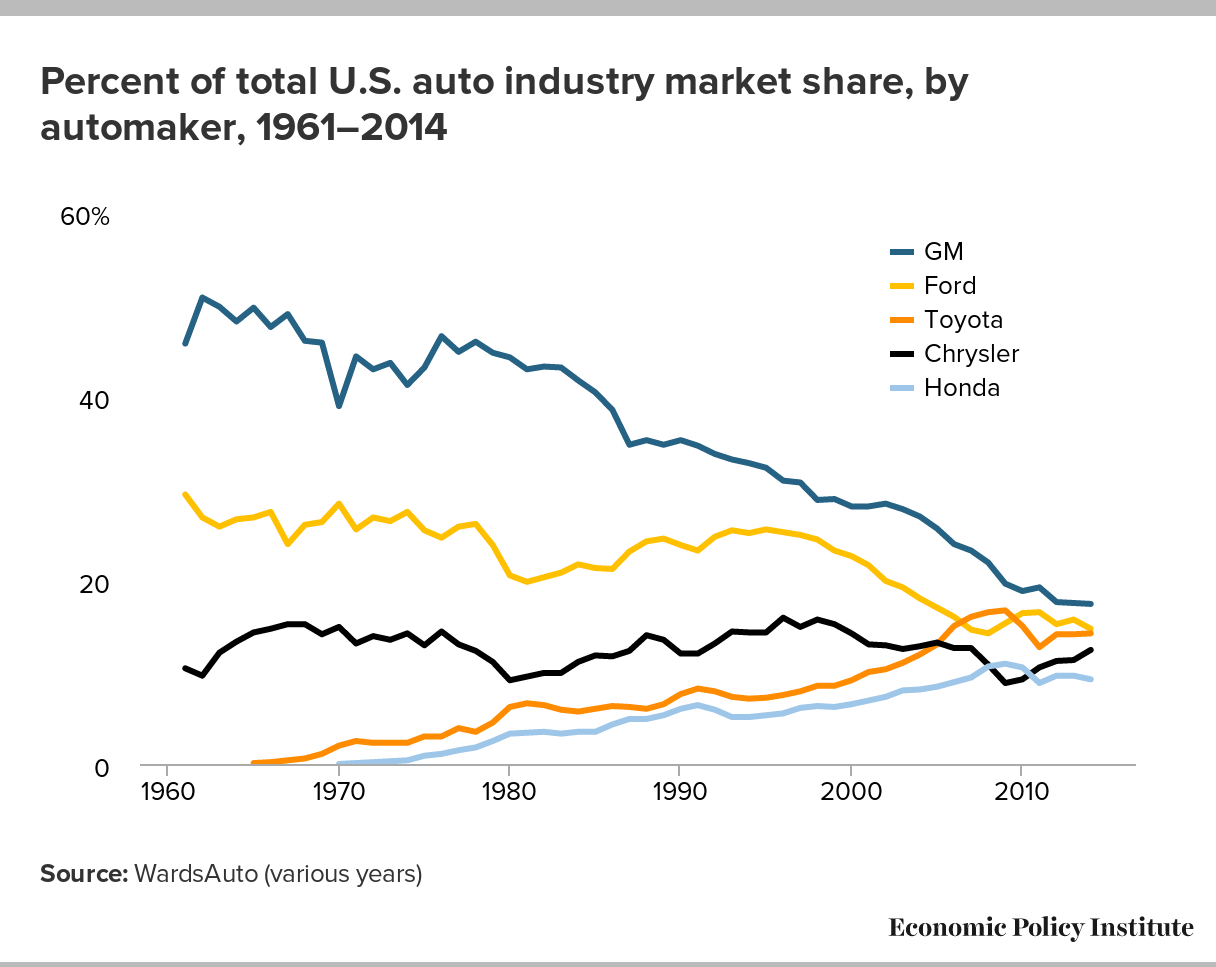

My recent fascination with understanding the auto sector comes from the observation that a country’s position in the global economy seems often to be linked to the competitiveness of its auto industry. This was certainly true when the United States first pioneered the mass production of cars and became the world's industrial powerhouse in the early-to-mid 20th century. It was true again with Germany developing its manufacturing dominance in the postwar decades, and then with Japan's rise in the 1980s as a new global leader on the market.

If dominance in automotive manufacturing is a good heuristic for a country's economic strength, then the EV revolution must be considered one of the defining contest of the 21st century. And in this new race, China has outpaced previous incumbents, position itself at the forefront of the EV revolution.

Each time a new leader emerged, they did so not only because of new technological innovations but because they pioneered new organizational strategies that allowed them to build cars more efficiently, flexibly, and competitively than their rivals. In this aspect as well, EVs are no exception. As I've written in previous posts, the top EV makers (most of all BYD) today depart from the more fragmented supply chains of the past few decades and are instead vertically integrated behemoths. But as new players enter into the market, greater variation in firm strategies are also emerging. There seems to be, at this time, no one best strategy that EV makers are conforming to.

This post is traces how firm structures in the auto sector have evolved over time—in particular how automakers puruse different approaches to labor and supply chain governance in order to stay competitive. It offers a brief (and mostly American) overview of that history, from Fordist mass production to lean manufacturing, modularization, and finally to today’s unsettled EV landscape.

Fordism and the rise of mass production

The mass production of automobiles began in the United States in the early 20th century under the Fordism mode of production. Since I've written about Fordism in a previous post, we can forego a lengthy discussion of it here.

In short, Fordism was defined by massive, vertically integrated supply chains housed within geographically anchored corporations that were both labor- and capital-intensive. These production sites carried high fixed costs and employed large numbers of workers, making them especially vulnerable to labor unrest. To mitigate this risk, Fordist firms maintained stable relationships with labor unions and shared the gains from automation and rationalization, ensuring a degree of labor peace and long-term productivity growth.

Under this arrangement, unionized workers enjoyed high wages, job stability, and generous benefits, while employers had strong incentives to invest in machinery and production techniques to increase productivity over time. Labor and capital thus held each other in check, creating a stable and relatively equitable model of industrial production. The problem with the Fordist model, however, was that production was highly standardized and relied on relatively low-skilled, assembly-line tasks—leaving little room for bottom-up innovation.

The lean manufacturing revolution

The Fordist model broke down in the post war decades, as German and Japanese automakers emerged as formidable global competitors. The rise of Japanese firms, in particular, marked a decisive shift away from rigid vertical integration toward what came to be known as lean manufacturing—most famously described in James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos's 1990 landmark book, The Machine That Changed the World, which remains the definitive account of Toyota’s transformative production system.1

Whereas Fordist production prioritized the mass output of standardized, homogenous products with minimal variation in design, Japanese automakers like Toyota pioneered a more flexible approach that could adapt to diverse market niches and shifting consumer preferences. Emphasis was placed on continuous, incremental process innovation at every stage of the supply chain. And workers played an active role in identifying bottlenecks, solving problems, and proposing improvements—breaking down traditional hierarchies and embedding innovation into daily operations.

Under the new lean manufacturing paradigm, supply chains became more decentralized and relational, composed of networks or "families" of specialized firms. These systems relied on long-term collaborative partnerships and extensive information sharing, particularly with competent first-tier suppliers who could independently innovate while remaining closely coordinated with lead manufacturers.

One best way?

The rise of lean manufacturing in Japan hit American automakers with billion in combined losses, and by the early 1990s, Ford, Chrysler, and GM began implementing lean practices. This new paradigm touched nearly every part of these American firm’s production strategy—from the factory floor to supplier relations, workforce organization, and engineering design.

A 1992 Wall Street Journal article documented Chrysler’s efforts to reform its internal labor structure.2 Taking cues from Honda, the company dismantled organizational silos separating engineering, design, and marketing, and introduced mechanisms for bottom-up innovation. Employees at all levels and in all departments were now expected to contribute to process improvements—a radical departure from Chrysler’s previously more top-down model.

To Womack and his co-authors, these changes were expected as they saw lean manufacturing as a universally superior system that all automakers would eventually converge on. But while these efforts produced some tangible gains, wholesale adoption of the lean paradigm proved difficult for these U.S.-based automakers.

In the United States, shareholder pressure for short-term returns (a product of the Shareholder Value Revolution, which I've written about here) undermined efforts to build durable, trust-based supplier relationships. Firms like Ford and GM reverted to outsourcing strategies built on inter-supplier competition, maintaining arm’s-length ties that prioritized cost-cutting over co-development.

Since then, new evidence challenged the convergence assumption. Auto manufacturing continued to vary significantly across countries—a divergence shaped by deeply embedded national institutions, including labor laws, vocational training systems, corporate governance structures, and long-standing social compacts between labor and capital (see One Best Way? by Freyssenet et al., 1998).3

Modularization

By the 1990s and 2000s, as the industry began to design vehicles around standardized and interchangable parts, the auto industry embraced yet another paradigm: modularization.

Under this model, cars were broken down into distinct modules—such as the chassis, powertrain, and interior systems—that could be developed and assembled semi-independently. Each module followed standardized design interfaces, enabling different suppliers to work on components in parallel while ensuring compatibility at final assembly.

Crucially, modularization also made it easier for lead firms to outsource key parts of the production process to a broad network of arm's-length suppliers without requiring the tight, long-term relationships characteristic of the Japanese supply chains. But in doing so, it also forfeited some of the dynamic learning and process innovation potential that lean manufacturing had harnessed.

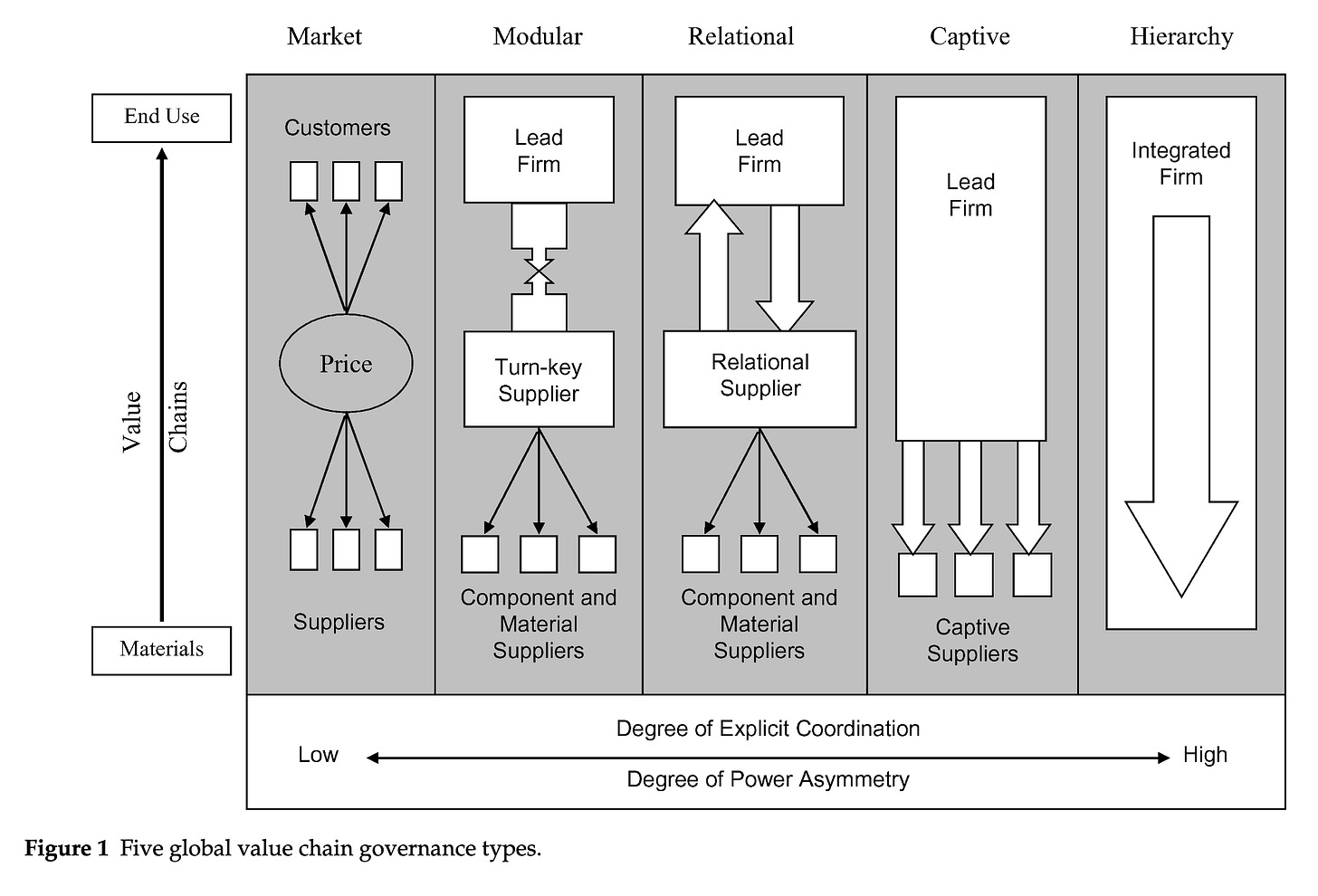

The diagram below offers a useful typology to trace this historical evolution in supply chain governance.4 The Fordist model, situated on the far right, is best described as hierarchical or captive, with tightly controlled, vertically integrated supply chains concentrated within a single firm. Then, over the next century or so, production systems have moved progressively to the left. Lean manufacturing introduced more relational forms of coordination, emphasizing long-term collaboration and trust-based ties with a smaller number of key suppliers. This eventually gave way to modular supply chains, where standardized interfaces allow for loosely coupled relationships and greater supplier autonomy—prioritizing flexibility, cost efficiency, and ease of substitution over deep inter-firm integration.

The EV Transition

Since the era of modularization, frontier corporate strategies in the automotive sector had remained relatively stable. But with the rise of EVs, automakers are once again forced to rethink their production strategies.

From a supply chain governance perspective, what’s most striking about the EV transition is the revival of vertically integrated production models reminiscent of the Fordist era. Leading the way in this are BYD and Tesla—both of which control a substantial portion of their value chains, from battery cell production and vehicle assembly to proprietary software development.

Yet as the battery technologies mature and legacy automakers enter the market, alternative strategies are also gaining traction. Companies like Ford and Volkswagen have maintained modular supply chains, especially with battery manufacturers. Batteries are also now the most complex, valuable, and strategically critical component of EVs; they are also highly modular. This has tilted power away from traditional automakers and toward a new class of specialized battery markers, particularly in Asia, where firms like CATL, SK Innovation, LG dominate.

Between the vertically integrated first movers (Tesla and BYD) and the more modular approach of legacy carmakers (Ford and Volkswagen), what the best model is remains an open question. It is also one that will also be contingent on the national institutional contexts in which the lead-firm is situated in.

If a country’s position in the global economy is linked to the competitiveness of its auto industry, then understanding how firm strategies are evolving in the EV age must be considered one of the most consequential—and still unfolding—questions in industrial strategy today. And it’s an evolution I’ll continue to follow closely and write about here on Value Added as the sector matures and the contours of the next industrial era take shape.

Womack, James, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos. 1990. The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production. Free Press.

Bradley A. Stertz. 1992. “Importing solutions: Detroit's new strategy to beat back Japanese is to copy their ideas --- firms streamline processes all along the line, led by a born-again Chrysler --- cutting out wasted motion.” Wall Street Journal

Freyssenet, Michel, Andrew Mair, Koichi Shimizu, and Giuseppe Volpato, eds. 1998. One Best Way?: Trajectories and Industrial Models of the World’s Automobile Producers. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Gereffi, Gary, John Humphrey, and Timothy Sturgeon. 2005. “The Governance of Global Value Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 12(1): 78–104.

Great Article! The tension between vertical and decentralized integration is articulated really well. Autonomy is also driving the shift toward vertical integration, driven by the need to control the proliferation of sensor systems necessitating more complex ECUs. This complexity makes it harder to outsource to sub-suppliers. Maybe partnerships such as the recently announced Lucid/Uber/Nuro link-up may emerge as alternative?