The rise of tech worker activism

My new ILR Review article shows how political/social protests turned into class conflict inside the tech industry. It sets the stage for understanding labor relations in the tech sector today.

I’m excited to share a new research article that I co-authored with Natalia Luka and Emily Mazo—two close friends, collaborators, and longtime interlocutors on everything related to labor in the US tech sector. The article draws from years of conversations, a dataset of collective actions in the tech sector that we’ve collective built and maintained, and a mutual interest in understanding why tech workers came to be organizers. In this short post, I’ll highlight some of its key findings.

Argument in short

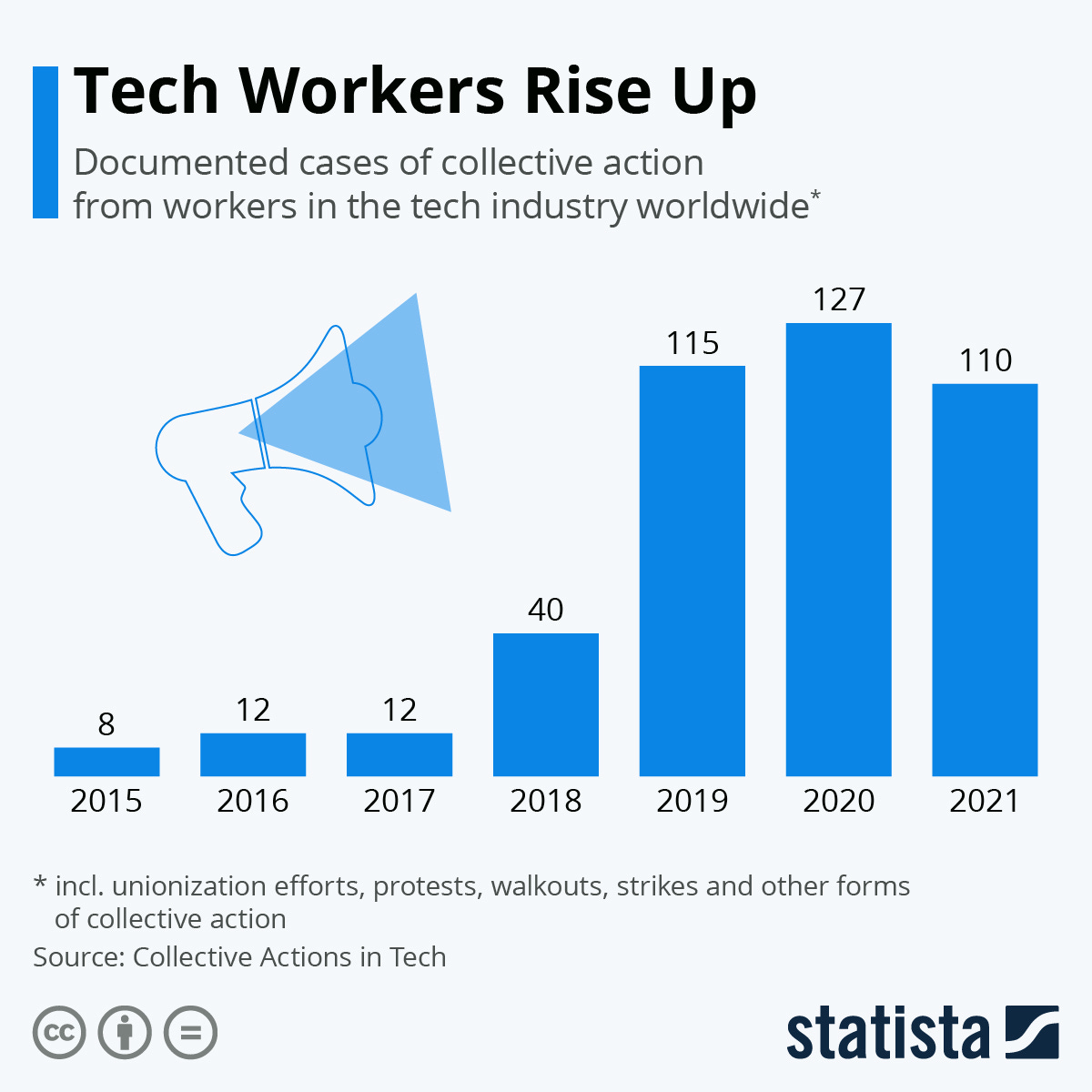

This basic premise of this article begins with a puzzling trend: since 2018, organizing efforts have grown within the tech sector, led not by the typical ranks of exploited or low-wage workers, but by highly paid, technically skilled professionals—engineers, designers, data scientists, etc.

Traditionally, labor organizing is a way for the most exploited workers in society to fight for better pay and working conditions—for example, factory workers in the auto industry have long organized around issues like low wages, dangerous working environments, and long hours, leading to landmark union contracts that reshaped industrial labor standards in the 20th century.

Tech workers sit far outside the traditional image of the exploited laborer. They earn some of the highest salaries in the country and enjoy comfortable jobs with lavish perks—free meals, game rooms, on-site massage therapists, nap pods, and even cooking classes. And unlike the typical factory worker, tech workers also have a high degree of autonomy, often setting their own schedules, working remotely, and facing minimal direct supervision.

All of this makes tech professionals seem like unlikely candidates for labor organizing. And indeed, labor relations in the US tech sector was relatively stable and pro-worker for most of the 2000s and 2010s.

Yet, over the past few years, tech workers have increasingly turned to organizing—and not just in isolated cases. In 2019, software engineers contracted through HCL Technologies at Google successfully formed what became the first recognized union of its kind in the United States. The next year, workers at Kickstarter also won their union drive. The tech division at the New York Times also voted overwhelmingly to unionize. Today, there are more than two dozen unions representing tech workers that have been officially recognized.

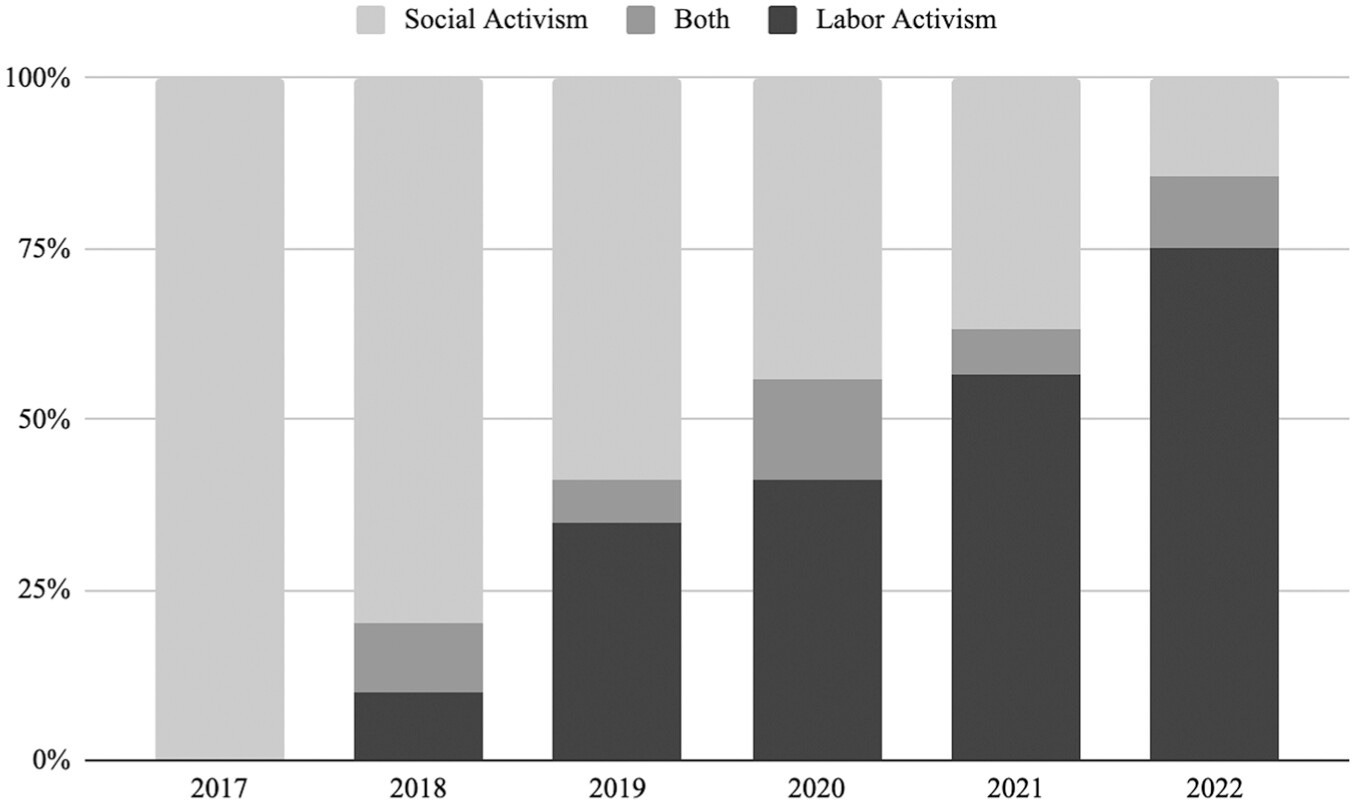

To understand the rise of labor activism in tech, we analyzed all publicly documented instances of collective action by US tech workers (which we’ve made public here) from 2014 to 2022. We found that tech workers engaged in both traditional labor activism and what we call social activism—actions over issues like military contracts that don’t directly affect their own pay or conditions. Our article then uses a logistic regression with company fixed effects to test how these different forms of activism relate to each other and how organizational characteristics shape their likelihood.

The central finding of our article, and what our regression analysis confirms, is that participation in social activism often served as a catalyst for more durable labor organizing within the sector. When employees faced retaliation or clashed with management, many began to recognize their shared vulnerability—not as individual professionals, but as workers. These experiences pushed them toward organizing for stronger protections and better working conditions. In other words, tech labor organizing builds on earlier waves of struggle. It’s a reminder that engaging in conflict can clarify class position and beget further conflict.

Or, as we say quite nicely in the article:

Participation in [social/political] activism generates solidarity among employee-participants. It can also create conflict with management, who see such protest strategies as tarnishing the company’s brand image. In this way, social activism exposes the previously hidden divide between workers and management, masked by the industry’s techno-utopianism.

Backlash against tech labor uprising

One of the recurring themes of this newsletter is tech labor—and, more broadly, how certain labor arrangements can shape innovation. I’ve argued, in fact, that stable, inclusive, or even empowering labor arrangements, can benefit innovation outcomes. But just as revealing are the breakdowns. The most extreme cases—the moments when labor relations collapse—offer critical insight into what happens when the foundational social contracts that underpin innovation go through an upheaval. In a sense, this article sets the stage for one of those breakdowns.

If the years between 2018 and 2022 marked a flowering of labor organizing in the tech sector, the years since have seen an unmistakable backlash. Rising inflation in 2022 meant the end of the zero-interest-rate-policy, giving tech employers a chance reset labor relations in the industry and dismantle the very conditions that gave rise to the tech labor movement. As we show in our paper, this hasn’t led to the death of labor organizing in the industry. Still, its impacts are far reaching.

Since then, mass layoffs have wiped out tens of thousands of jobs. The very departments that once embodied a more socially conscious tech culture—trust and safety, AI ethics, etc—have also been purged. Diversity and inclusion programs have been dismantled. Internal communication channels once used for open debate have been restricted or shut down altogether. The latest iteration of this hostility comes from the AI startup world, where some founders have openly taken a page from China’s infamous “996” work schedule—9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week (and I’ve written here about how this kind of work model has shaped innovation in China’s internet sector). All of this has made workers more precarious and less willing to organize.

This shift could have a major impact on innovation in the tech sector. A culture of fear and overwork can yield short bursts of productivity, but it in the longer term, it corrodes the trust, creativity, and critical exchange that breakthrough innovation requires. As I’ve written about before, DeepSeek was actually among the only Chinese tech companies that didn’t enforce 996 and other draconian labor practices that were ubiquitous in China’s tech scene, contributing in part to its breakthrough success.

It’s too soon to know exactly how this new age of tech labor austerity will play out. The effects aren’t uniform either—AI researchers get far more leeway than most software engineers. Still, it’s a dynamic worth watching, especially as the US economy bets so heavily on continued breakthroughs in AI.

Another angle to view the rise of tech worker unionization is an effort to resist or blunt the effects of AI from a worker perspective. This lens has parallels with automotive unions.

Article request: Curious about your thoughts on earlier eras of tech worker organizing and union power, like the Communications Workers of America on their rise in the 1960s, particularly as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, as the new major private ICT utilities are increasingly structuring public systems.