Innovation without invention

What the data shows us about AI innovation in the U.S. and China.

The AI news cycle about China can be overwhelming and confusing. The narrative can swing wildly with each model breakthrough. One day, the U.S. is portrayed as maintaining an unshakable lead. The next, China is hailed as the world’s new AI superpower. These seemingly contradictory claims, however, are often both true. But that truth hinges on what we mean when we say "ahead" and how we choose to measure it.

Indeed, evaluating how advanced a country is in a broad technical domain like AI is not trivial. For instance, whether a country has the capabilities to produce new AI model paradigms requires vastly different capabilities from making incremental improvements on existing models. And both differ again from a country’s ability to diffuse AI across an economy and drive productivity gains. The point is that the "AI race" isn't being run on a single lane.

In this post, I use Epoch AI's dataset1 of notable models to take a systematic look at the past decade of AI innovation and to see where China and the United States stand and what each of their strengths are. And as we shall see, where the two countries stand in AI innovation is much more nuanced than what most media outlets tend to portray.

Before diving into our comparison, let me first highlight that the following analysis (unless otherwise stated) is limited to AI models that are published by industry players. The reason I do not focus on academic institutions is because industry is overwhelmingly the primary producers of notable AI models according to the database2, so if the following analysis were to have any predictive value, then including academic contributions may end up only creating noise.

The U.S. is the clear leader but China is rapidly catching up

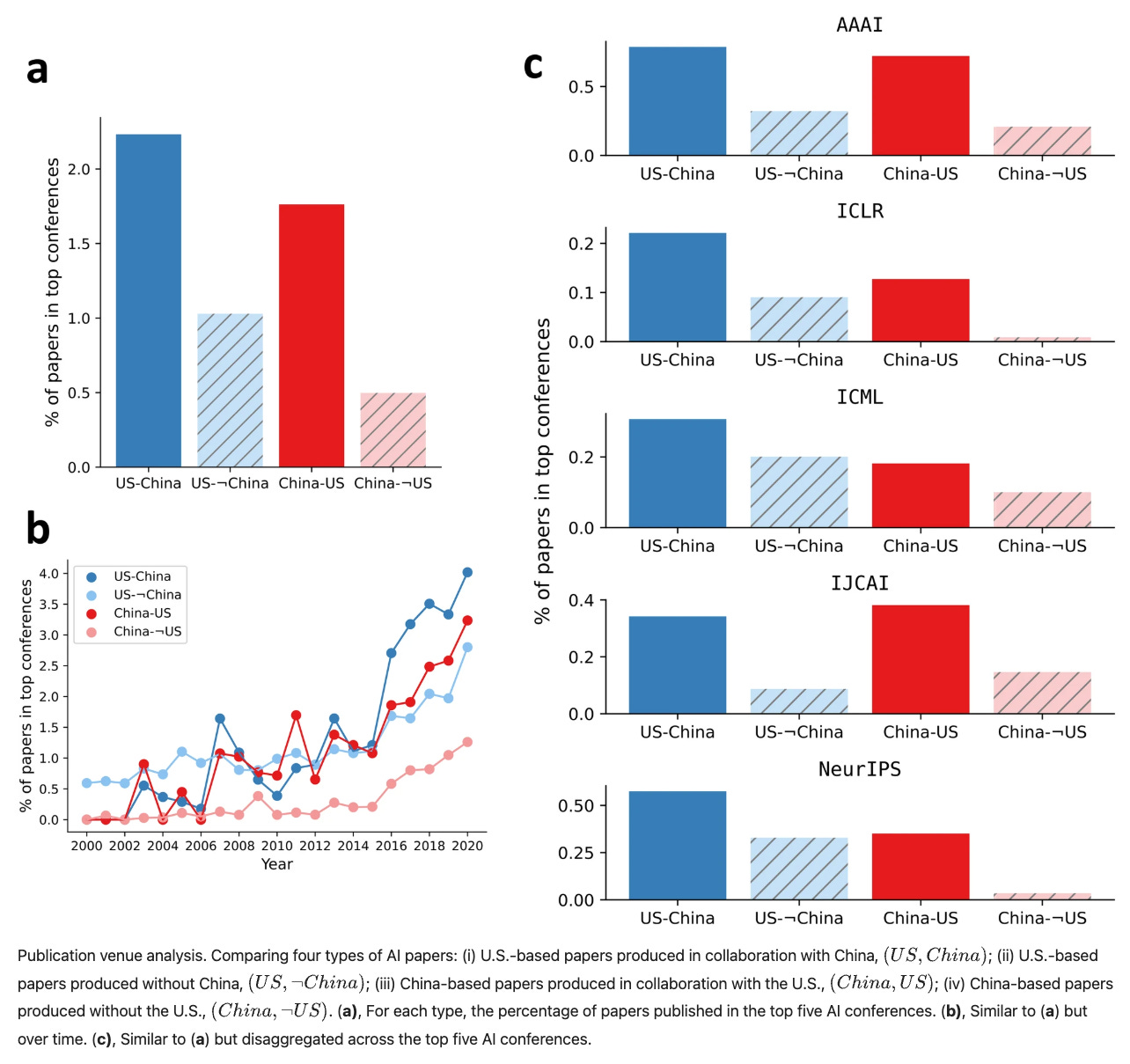

For several years, scholars and journalists have pointed to China’s rapid catch-up with the U.S. in the sheer volume of STEM research output. However, they’ve also noted that the quality of this research (often measured by acceptance into top conferences or citation counts) has continued to lag behind.3

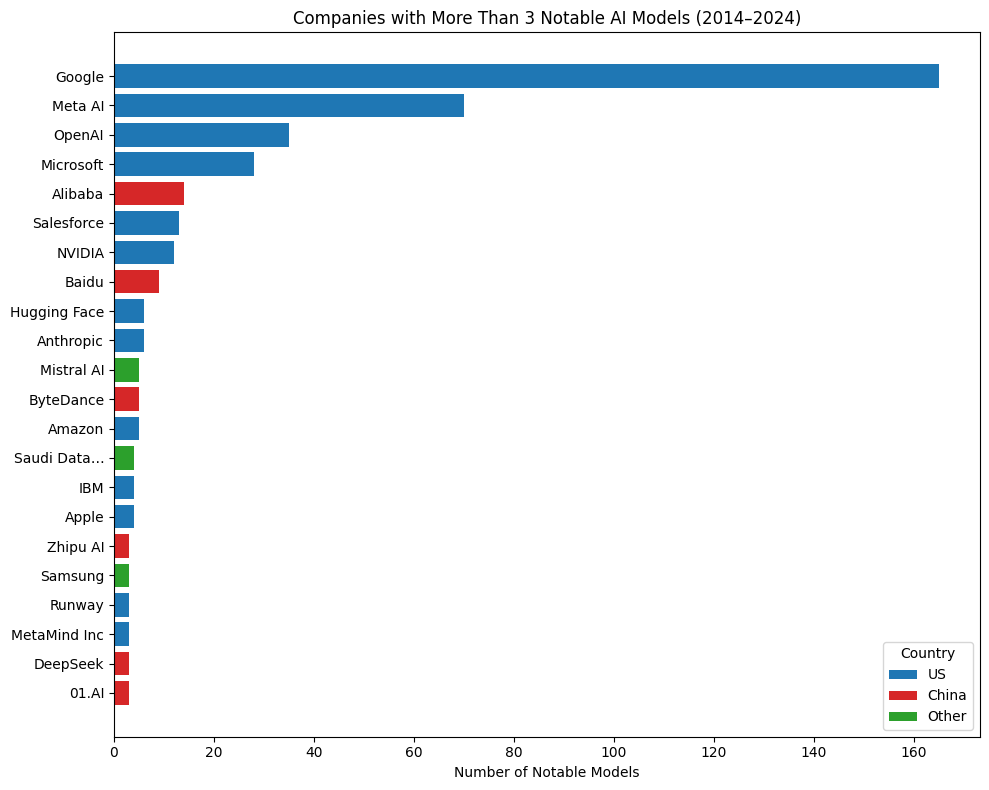

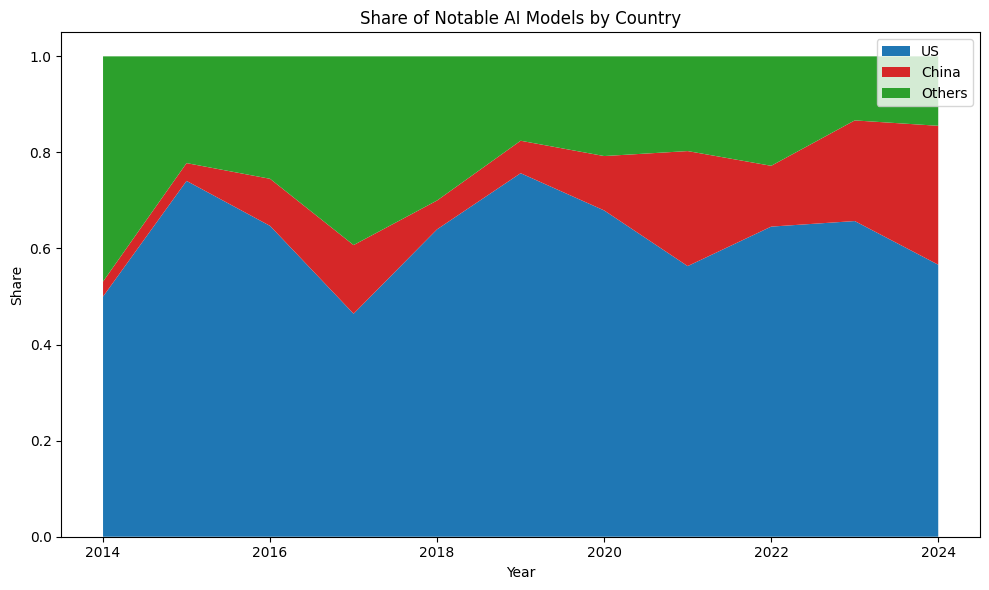

The pattern holds true in AI as well. While the volume of AI research coming out of China has surged—surpassing the U.S. by some measures—the overall quality still lags behind. When we rely on Epoch AI’s classification of notability (which I’ll explain shortly), the U.S. remains the clear leader. Over the past decade, the development of high-impact AI models has been overwhelmingly concentrated in a small number of U.S.-based tech firms.

But a decade is a long time. When we look at the year-by-year trend, what we see is that since around 2019, Chinese firms have steadily increased their share of notable AI models, gradually chipping away at U.S. dominance in the field. By 2024, Chinese firms represent nearly 30 percent of notable models, up from just 6 precent in 2019. If the trend continues, we should expect to see China playing a far more dominant role in producing notable AI models in the coming years.

This is a bit of a side point, but I think its also worth emphasizing that innovation doesn’t have to be a zero-sum race. Recent research shows that cross-country collaboration can in fact yield the best research outcomes in AI. Using data since 2000, a recent Nature report shows that American and Chinese researchers (including academic researchers) produce more impactful AI research on average when they collaborate with each other.4

Varieties of AI innovation

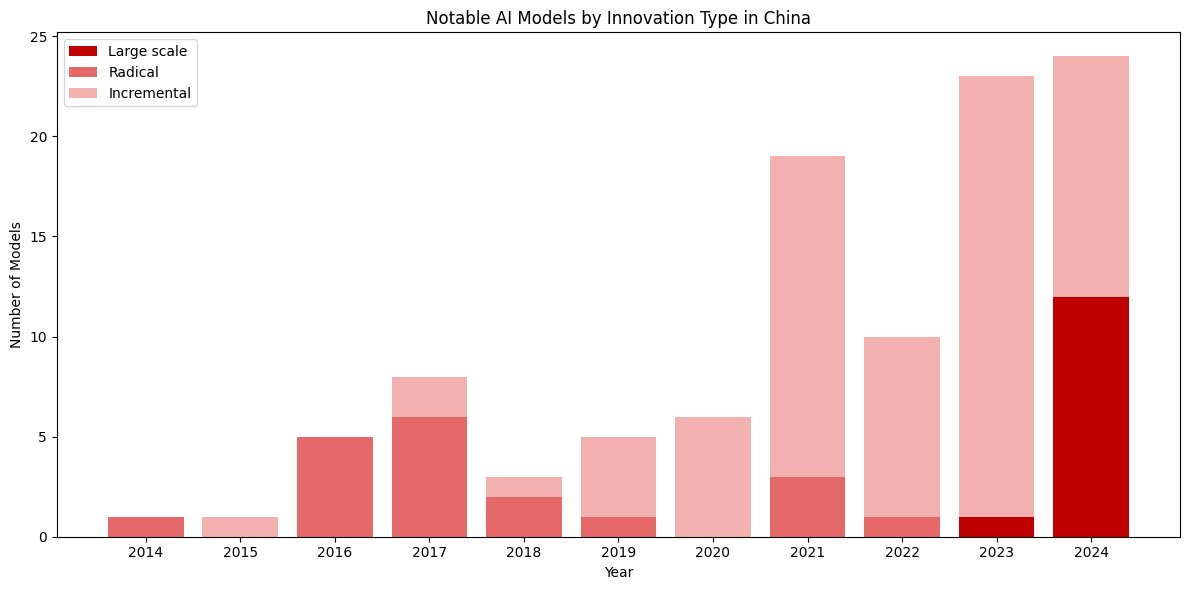

So far, the data shows that China is emerging as an increasingly important player, not only in the overall volume of AI models it produces, but also in its growing share of notable models. However, even within what are considered “high impact” or “notable” AI models, there is important variation that we should pay attention to. Epoch AI uses four different criteria to satisfy their standard for notability. The first is whether it has received more than 1,000 citations. The second is whether it holds indisputable historical significance (e.g., AlexNet, GANs). The third is whether it has more than one million active users. And the fourth is whether it represents a clear improvement on the state of the art (SOTA).

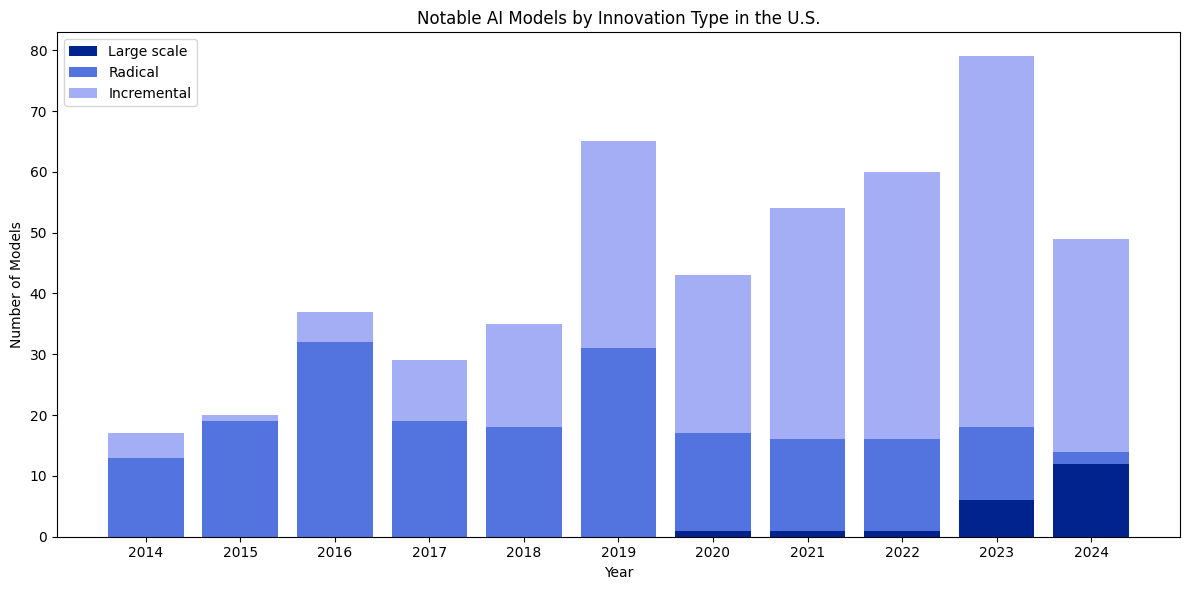

We can use the first two indicators (high citations and historical significance) as proxies for radical innovation, since these typically reflect paradigmatic breakthroughs that shift some aspect of the trajectory of the field or opens up entirely new research directions. The latter two (high usage and improvements on the SOTA) can serve as proxies for incremental innovation since they are about optimizing and improving upon existing models and building widely adopted applications on top of that.

The dataset also tracks another category of notable models: models with training costs exceeding $1 million. This metric does not strongly indicate whether a model represents radical or incremental innovation. Instead, it reflects scale and whether an organization has the financial and technical resources to support large AI training efforts.

When we split up the number of notable AI models into these categories, we see that the vast majority of China’s growth in AI innovation comes from incremental innovation and scale. The number of AI models in the domain of radical innovation remains low with no sign of growth.

One important limitation of this dataset is that using citation counts introduces a bias against more recent models. Whereas an improvement on the SOTA is normally immediately apparent (and is usually articulated in the model’s corresponding research paper), reaching 1,000 citations takes time, so recent breakthroughs no matter how notable may be excluded simply because they haven’t had the time to accumulate citations. Moreover, we may also expect a shift from radical to incremental innovation in AI since there may simply be less room for continued radical innovation as the technology matures.

That said, when we examine the breakdown for U.S.-based firms, we see that while the number of models representing incremental innovation has increased over time, there remains a relatively stable foundation of radical innovation, with around 20 highly cited or historically significant models produced each year. This suggests that the U.S. maintains a unique capacity for radical innovation in AI that China lacks.

China's focus in diffusion-oriented innovation

The relative lack of radical innovation in China shouldn’t be mistaken for a lack of creativity or ambition. Rather, China’s capabilities in incremental and process-oriented innovation reflects a broader strategic focus on the diffusion (rather than the invention) of new technologies. And as a result, this approach enables more actors across the economy to share in the productivity gains that these technologies make possible. In other words, this mode of innovation delivers real dividends in sustainable economic growth, industrial upgrading, and technological sovereignty.

By contrast, the U.S. innovation system has long prioritized and rewarded radical, zero-to-one innovation. Strong intellectual property protections incentivize breakthrough inventions by granting exclusive rights to early movers. Likewise, the country’s approach to industrial policy has focused on pushing the technological frontier. Agencies like DARPA, for instance, are explicitly tasked with funding projects that are 10 to 15 years ahead of mainstream commercial adoption.

Some scholars have argued that Chinese companies excel in what’s often called “second-generation” or “applied” innovation which focuses on incremental improvements to products, processes, or manufacturing techniques. Dan Breznitz and Michael Murphree, writing in 20115, observed that Chinese firms often operate at the edge of the technological frontier without necessarily pushing it forward. They find that firms don’t need to be radical innovators to succeed. Rather, it’s often enough to make products cheaper, faster, more precisely, and at higher quality.

This theory has largely played out across several strategic sectors in China. In batteries, solar photovoltaics, electric vehicles, and semiconductors, Chinese firms have become global leaders not by inventing entirely new technologies, but by mastering and refining existing ones at scale. And as the data above shows, this also appears also to be the trend in AI with Chinese firms excelling not in entirely new frontier models, but in incremental improvements on SOTA models.

DeepSeek is an example of this—not pushing our imaginary of what LLM-based AI models can do, but making it significantly cheaper and more efficient to train. And as in the case of other industrial sectors, this mode of innovation lends itself better to the diffusion of technology. Since the release of DeepSeek, we've seen uptake of their more inexpensive model across China”s digital ecosystem.

That said, China faces different challenges when it comes to AI diffusion. The main issue is that internet companies like Alibaba and Tencent are the primary engines of AI diffusion in China. As Grace Shao and I have explained, this means adoption is likely to remain concentrated in consumer-facing applications as these internet firms have built their core strengths around platform services for individual users, not enterprise clients. In contrast, the U.S. has a long history of building enterprise software, along with higher overall business investment in IT and digital tools- giving U.S.-based AI firms a clearer path to driving adoption across a wider range of industries.

There’s a bit of irony in this. Since 2021, the Chinese state has tried to pivot away from “soft tech” sectors—consumer-facing platforms like e-commerce, food delivery, and social media—and instead prioritize “hard tech” domains such as advanced manufacturing, renewables, and other drivers of industrial productivity. In this plan, advanced technologies like AI are meant to accelerate this transition from soft-to-hard sectors. So the fact that it’s only the internet giants that have the real technological capacity to innovate on and diffuse frontier AI models probably isn’t exactly what Beijing had in mind.

Epoch AI, ‘Parameter, Compute and Data Trends in Machine Learning’. Published online at epoch.ai. Retrieved from: ‘https://epoch.ai/data/notable-ai-models’

Academic institutions consistently produce between 20 and 30 notable AI models each year. In contrast, industry output was comparable in the mid 2010s but has surged over the past decade, reaching nearly a hundred notable models in the past two years.

Scholars have demonstrated that political competition among localities has resulted in the proliferation of low-quality patents as a way to boost local gov metrics (See Ang, Yuen Yuen, Nan Jia, Bo Yang, and Kenneth G. Huang. 2023. “China’s Low-Productivity Innovation Drive: Evidence From Patents.” Comparative Political Studies). A similar dynamic may apply to the increase in low-quality STEM research papers.

See AlShebli, Bedoor, Shahan Ali Memon, James A. Evans, and Talal Rahwan. 2024. “China and the U.S. Produce More Impactful AI Research When Collaborating Together | Scientific Reports.” Sci Rep 14. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-79863-5#Fig4

See Breznitz, Dan, and Michael Murphree. 2014. Run of the Red Queen: Government, Innovation, Globalization, and Economic Growth in China. New Haven London: Yale University Press.

A well research and written piece, pointing out the comparative advantages of the two different approaches. Many a times when leaders in different value chain can cooperate and complement each other and work together would benefit overall industry.

Huawei might be the only exception who is leading AI in China not being an internet company