How Every Superpower Stole Its Way to the Top

The U.S. stole its way to the top—now it's trying to stop China from doing the same.

Imagine a city that has become an industrial powerhouse. Machines run day and night, six, sometimes even seven days a week, churning out increasingly sophisticated goods for global markets. Its success has brought economic prosperity not only to itself but to its entire nation. But the technology underpinning this boom didn’t emerge out of nowhere. It was stolen—copied from a more advanced nation and adapted for local production. This was the foundation upon which this city became the factory of the world. I’m not talking about Shenzhen, China. No, this was Lowell, Massachusetts, in the 1850s.

Since China has emerged as a formidable economic competitor, the U.S. has accused the country of playing dirty—stealing intellectual property, coercing technology transfers, and using state-backed industrial policies to gain an "unfair" technological edge. American policymakers insist that China’s rise in tech isn’t the result of genuine innovation but of illicit tactics.

This framing has justified an escalating series of restrictions to curb Beijing’s progress: trade blacklists, investment bans, and sweeping export controls aimed at crippling China’s access to advanced technologies like semiconductors and AI. Earlier this year, Chinese AI startup Zhipu was added to a trade blacklist that restricts it from buying American technology. This follows sweeping bans on the export of advanced semiconductors aimed at crippling China’s AI ambitions.

But if we look at the history of industrial development, China’s efforts to get its hands on foreign technologies are far from unique. Every major economic power—including the U.S.—built its technological base by acquiring and adapting innovations from more advanced nations. More often than not, this process involved industrial espionage, strategic imitation, and state-backed efforts to close the technological gap. In this way, China is not an outlier but a follower of the same playbook that propelled today’s advanced nations to the top.

The long history of gatekeeping technology

The diffusion of technology has long been considered an essential ingredient for developing countries to catch up. Since it can be assumed that technology is “borrowed” or “learned” rather than reinvented in each country, the degree to which new technology is diffused would, in theory, correlate to a developing country's ability to catch up. In other words, if technology diffusion were perfectly frictionless across borders, developing countries would quickly catch up to advanced economies.1Yet, despite globalization and unprecedented connectivity, developing countries have not been able to catch up to advanced economies.

Since the industrial revolution, leading economies have actively blocked technology transfer to entrench their dominance. Advanced nations do not only rely on innovation to stay ahead; they have historically used legal, economic, and political tools to prevent rising competitors from catching up.

19th century Britain, the world’s first industrial superpower, provides a striking historical parallel to today’s U.S.-China tensions. As development economist Ha-Joon Chang details in his aptly titled book Kicking Away the Ladder, Britain responded to growing competition from countries like the U.S. and Germany with a range of restrictive policies designed to curb the diffusion of its industrial technology.2

For its colonies, Britain pursued a deliberate strategy of industrial suppression. It kept these territories as raw material suppliers rather than allowing them to develop their own manufacturing base. British authorities went as far as banning key manufacturing activities, for example, outlawing the construction of rolling and slitting steel mills in America to ensure that producers could only export low-value pig and bar iron rather than finished steel products that could compete with British manufacturers. Exports that threatened British industries were banned outright as was the use of tariffs for infant industry protections.

In other countries, Britain blocked efforts to industrialize through the use of unequal treaties. These treaties imposed strict tariff ceilings, typically around 5% making it impossible for them to nurture local manufacturing. Britain first used this strategy in Latin America, starting with Brazil in 1810, ensuring that these economies remained dependent on exporting raw materials while importing British manufactured goods. A more infamous example came in China, where Britain imposed the Treaty of Nanking (1842) after defeating China in the First Opium War. Among its many provisions, the treaty forced China to surrender control over its tariff policies, leaving it unable to shield domestic industries from foreign competition. Political economist Alice Amsden argued that countries were only able to begin industrializing in earnest after regaining tariff autonomy—an advantage Britain worked hard to deny its potential rivals.3

For independent competitors like the France and Germany, Britain took a more direct approach—limiting the outflow of technology itself. Recognizing that industrial expertise was just as valuable as machinery, Britain passed strict laws to prevent skilled workers from leaving the country. As early as 1719, British law prohibited craftsmen from emigrating, imposing severe penalties on those who defied the restriction, including the loss of citizenship and property. At the same time, Britain heavily restricted the export of industrial machinery, particularly in strategic industries such as textiles, steel, and shipbuilding.

This strategy of restricting technology transfer is not a relic of the past—it is being actively revived today. In 2022, the Biden administration prohibited U.S. citizens and green card holders from working for Chinese semiconductor firms, effectively weaponizing human capital controls to limit the flow of expertise. At the same time, Washington has pressured key allies—such as the Netherlands and Japan—to impose export restrictions on semiconductor manufacturing equipment, ensuring that China remains locked out of the most advanced chip production technologies.

Industrial espionage is an American tradition

When dominant powers impose barriers—whether through export bans, immigration restrictions, or economic coercion—developing nations are often left with no choice but to seek alternative, sometimes illicit, means of acquiring the knowledge they need to advance. History makes this clear: industrial espionage has long been an unspoken yet vital tool for economic development.

This is precisely how the U.S., in its early years, caught up with Britain. In 1810, Francis Cabot Lowell, a Harvard graduate and Boston merchant, traveled to England, posing as a curious tourist visiting the country’s cutting-edge textile mills. At the time, textiles were the high technology of the industrial age—just as semiconductors are today—critical to economic power and global dominance. British authorities had long prohibited the export of textile machinery and the emigration of skilled workers, recognizing that their industrial supremacy depended on keeping these technologies under tight control. But Lowell, determined to bring this knowledge back home, carefully studied the designs of British power looms, then returned to the U.S., where he reconstructed them from memory.4

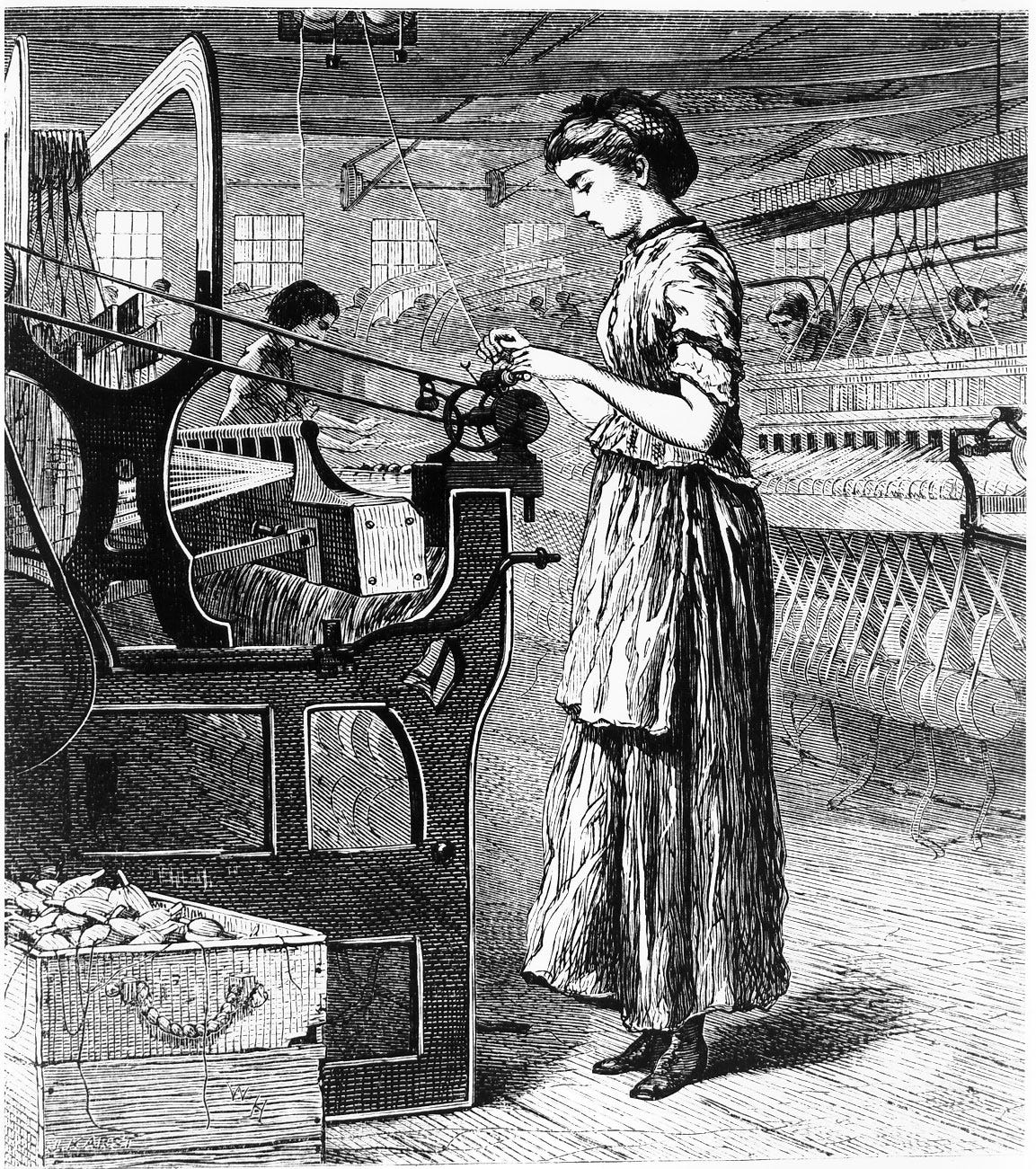

This act of technological theft laid the foundation for the American textile industry, giving rise to the industrial mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. Much like Shenzhen today, Lowell became the center of a booming industrial economy, its factories producing goods for export markets around the world.

Lowell wasn’t the first. Decades earlier, Samuel Slater (often called the “Father of the American Industrial Revolution,” or, in Britain, “Slater the Traitor”) an English-born cotton mill supervisor, had already set the precedent for industrial espionage.

Slater had worked in the British textile industry, where he became intimately familiar with the design and operation of the spinning machines that powered Britain’s dominance in cotton manufacturing. He oversaw Richard Arkwright’s patented spinning frames—one of the most advanced textile technologies of the time. Knowing that Britain prohibited the export of machinery—and that attempting to smuggle out blueprints would be nearly impossible—he memorized the designs instead. In 1789, he left for the U.S., where he reconstructed from memory the country's first water-powered textile mills.

The U.S. government actively encouraged industrial espionage in its early years, offering economic rewards for those who could bring foreign technological secrets into the country. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, in his 1791 Report on Manufactures, explicitly advocated for the recruitment of skilled workers from abroad and the appropriation of foreign innovations. This policy was reinforced by the Patent Act of 1793, which made it even easier for Americans to profit from stolen technology. Under this law, only U.S. citizens could receive patents, meaning that foreign inventors had no legal claim to their own innovations once they were copied and repurposed in the U.S.

As Pat Choate details in Hot Property: The Stealing of Ideas in an Age of Globalization, this system made the U.S. a pirate economy in its formative years.5 British and European inventors found themselves shut out of patent protections, while Americans freely took their ideas, modified them slightly, and claimed exclusive rights. Industrial theft wasn’t just tolerated—it was effectively institutionalized as a tool of national development.

Conclusion

The U.S. is far from the only country to have used industrial espionage as a strategy for economic catch-up. Germany, Japan, and South Korea all also used aggressive technology acquisition to drive their industrial rise. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germany reverse-engineered British and American innovations, particularly in chemicals and engineering. Post-war Japan followed a similar path, leveraging corporate intelligence, state-backed acquisitions, and strategic imitation to dominate automobiles and electronics. South Korea, in the 20th century, relied on forced technology transfers, outright copying, and state-driven industrial policy to become a global leader in semiconductors and shipbuilding.

Even before the Industrial Revolution, Britain itself benefited from stolen technology—ironically, from China. For centuries, China guarded the secrets of porcelain production, maintaining a lucrative monopoly on its exports to the West. Unsurprisingly, European nations wanted to manufacture porcelain on their own, leading to deliberate industrial espionage. In 1712, French Jesuit priest François Xavier d’Entrecolles infiltrated China’s porcelain industry, documenting its techniques in widely circulated letters.6 His reports detailed raw materials, glazing, and firing methods, enabling European manufacturers to replicate the prized ceramic ware. By the mid-18th century, Britain had developed its own porcelain industry, breaking China’s stronghold on the technology.

China today is simply the latest country to follow this well-worn path. Its technology policies—such as forced joint ventures, state-backed acquisitions, and cyber-espionage—are widely condemned by Western powers as violations of intellectual property rights. Yet, as history shows, every rising industrial power has used similar tactics to overcome the barriers imposed by dominant nations.

Theft and imitation have always been intertwined in the story of industrial development. Today, the U.S. is attempting to do what Britain once tried—gatekeeping its technology and keep a rising power from catching up. Whether it succeeds or fails remains to be seen. But if history is any guide, no technological empire lasts forever.

The degree to which technology is able to diffuse has been viewed as such a critical factor in development that some scholars argue that it is at the root of economic development. See: Easterlin, Richard. 1981. “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?” Journal of Economic History 41(1): 1–7.

Chang, Ha-Joon. 2002. Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem press.

Amsden, Alice. 2001. The Rise of “The Rest.” Oxford University Press.

The mills of Lowell were filled with young women and children, mostly from the countryside, who toiled for up to 14 hours a day in deafeningly loud factories, inhaling cotton dust that led to respiratory diseases—yet another similarity to the working conditions of factory workers in Shenzhen today.

Choate, Pat. 2007. Hot Property: The Stealing of Ideas in an Age of Globalization. Westminster: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Great post about how industrial espionage has fueled economic development globally for the past few centuries.

Brings to mind Bill Gates's response to Steve Jobs’ accusation that Microsoft stole from Apple by saying:

"Well, Steve, I think it’s more like we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it."

A very fun read!

I wrote a similar article a while ago as well. Industrial espionage was indeed an important part of economic development for many countries.

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/stealing-success-how-ip-theft-built

Modern IP laws enforced by the WTO and WIPO were created to protect the IP of creators and companies. So we have a global framework that prioritizes protecting the IP of advanced countries over allowing developing countries to pirate/steal/ascertain for technology transfer.