America can still build (data centers)

The Abundance thesis is that America can't build anymore, so how do we explain the surge of data center construction across the country?

From Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance agenda to Dan Wang’s lawyerly society, we’re increasingly told that America has lost the ability to build. Restrictive zoning laws, the story goes, choke off housing supply and underpin today’s housing crisis. Environmental reviews tie up new construction (like high speed trains) for decades. And the liberal impulse to give communities a say in shaping their neighborhoods has often enabled them to halt new projects in the name of preserving local interests. The result is a maze of local interests and procedural hurdles—reinforced by an army of lawyers and bureaucratic agencies—that has crippled America’s capacity to build, and especially to build big.

But if America has lost its ability to build, how do we explain the breakneck buildout of data centers? Underlying the AI revolution is the gargantuan building spree of data centers across the country. And in large part, such a buildout is powered by the cloud hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, who have each poured hundreds of billions of dollars (and billions of tonnes of concrete) into data center construction.

And in the truest sense, these data centers are about building big, with some now exceeding a million square feet—spanning the equivalent of more than 25 football fields—and commanding some of the largest construction budgets in the country. And unlike housing or high-speed rail, the United States is far ahead of China in data center construction and, with countless new projects already in the pipeline, is poised to maintain that lead well into the future.

You might argue that data centers are easier to build than new housing or transit lines because they have more flexibility in where they can be sited. There’s some truth to this, but hyperscalers aren’t building data center facilities randomly across the map either—they are converging on a limited set of geographies with the right mix of resources: abundant energy and water, cooler climates, and close to key high-speed fiber connectivity. These constraints drastically narrow the field of viable locations. And often, this means building takes place in exactly the kinds of places Abundance theorists insist are impossible—such as densely populated, liberal-leaning1 Loudoun County, Virginia (known as the “data center capital of the world,” with the highest concentration of facilities anywhere on the planet).

Herein lies the paradox. If America is unable to build—chasing software and finance instead of concrete and steel—then how has it managed to erect data centers at such speed and scale, far outpacing China, in what is now one of the largest infrastructure buildouts in the nation’s history?

Why corporate elites thrive in the American political economy

AI is now attributed to much of the buildout of data centers across the country. We should remember that data center has steadily expanded since the advent of cloud computing in the mid-2010s, long before generative AI went mainstream. But even if we accept that the AI boom has added fresh urgency, the Abundance thesis would insist that political motivation alone cannot overcome local interests and procedural gridlock—otherwise America’s housing crisis, which is nothing if not politically salient, would have been addressed long ago.

So the question then is why haven't data centers been stymied by the very forces that Klein, Thompson, and Wang insist has crippled America’s ability to build? To answer that, we need to step back and examine the country’s political system. Here, the emerging field of American Political Economy (APE)2 is especially useful for helping us understand why some actors are able to build while others are not.

APE highlights two features of the American political system that deserve close attention. First, it is exceptionally fragmented: authority is divided across multiple layers of government, and political contestation is spatially dispersed, decentralized, and played out across a wide range of venues. This creates a multitude of veto points and conflicting preferences, especially for projects or policies that span multiple jurisdictions. So even when there is broad political support for something like housing affordability, coordinating across venues can be prohibitively difficult, making ambitious national-level policy agendas hard to advance. Second, governance emphasizes local self-rule, which empowers local bodies like neighborhood associations, zoning boards, and city councils to wield outsized authority over decisions that carry national consequences. And when it comes to building new things, each of these local bodies can stall or even kill construction outright (which Abundance theorists also point to this as a root cause of the country’s building woes).

To navigate this political environment, APE identifies two decisive capacities. First, the ability to sustain long time horizons allows actors to outlast shifting coalitions, election cycles, and procedural delays that would exhaust if not outlast actors with shorter time horizons. Second, the ability to operate across multiple venues enables actors to coordinate in a federalized political system where coordination is otherwise difficult but essential for getting policy agendas passed. The capacity to operate across multiple venues also allows actors to engage in “venue arbitrage” such that if one jurisdiction resists, they can (threaten to) shift their investment to another. This creates competition among venues—states, counties, or regulators—which actors can exploit to extract better terms (e.g., bigger subsidies, looser permitting, etc).

These capacities are the hallmark of organized, well-resourced groups, and they explain why such actors thrive while disorganized, and poorly-resourced ones—renters, small developers, individual voters, and even local governments—rarely prevail. So while mass politics may have some influence, building large-scale policies requires sustained efforts by organized actors. This is why business and economic elites, above all the tech giants, have amassed such disproportionate political power in the United States.

How big tech sidesteps the red tape

Seen this way, we can start to understand why data centers (and not housing or high-speed rail) are bypassing restrictive zoning laws, circumventing red tape, and getting built. Unlike the individuals who voted for California High-Speed Rail or the diffuse (though national) constituency for more housing, tech giants are organized and well-resourced. They are armed with vast financial resources, professional lobbying operations, and long planning horizons. They also have the capacity to influence subnational governments across the country allowing them to play the multi-venue game with ease.

When it comes to building data centers, this dynamic plays out in two ways. First, tech giant hyperscalers can move between different arenas of decision-making and can thus exploit America’s fragmented political economy by engaging in venue arbitrage. If one county shows resistance, tech giants can threaten to exit and shop the project across localities for the best deal. And because of their largely oligopolistic market structure, they can operate across venues without competition. The result is a race to the bottom in incentives, as states and municipalities bid against one another with ever-larger tax abatements, cheaper land, and subsidized infrastructure hookups for the “privilege” of hosting data centers. Tech giants know this and use it to maximum effect, extracting the most favorable terms wherever they decide to build, allowing them in-effect to build at a discount.

Second, tech giant's ability to coordinate across the full spectrum of the American political system enables them to outmaneuver local opposition but shape the agenda at the federal level as well. They wield influence simultaneously at the state and county levels, as well as in Washington, where they lobby federal agencies and the White House. This ability to coordinate across venues has allowed their policy agenda to rise to the top—most clearly demonstrated by Trump’s executive order on “Accelerating Federal Permitting of Data Center Infrastructure,” which makes federal lands available, fast-tracks permitting, and encourages federal agencies to provide financial support for constructing data centers.

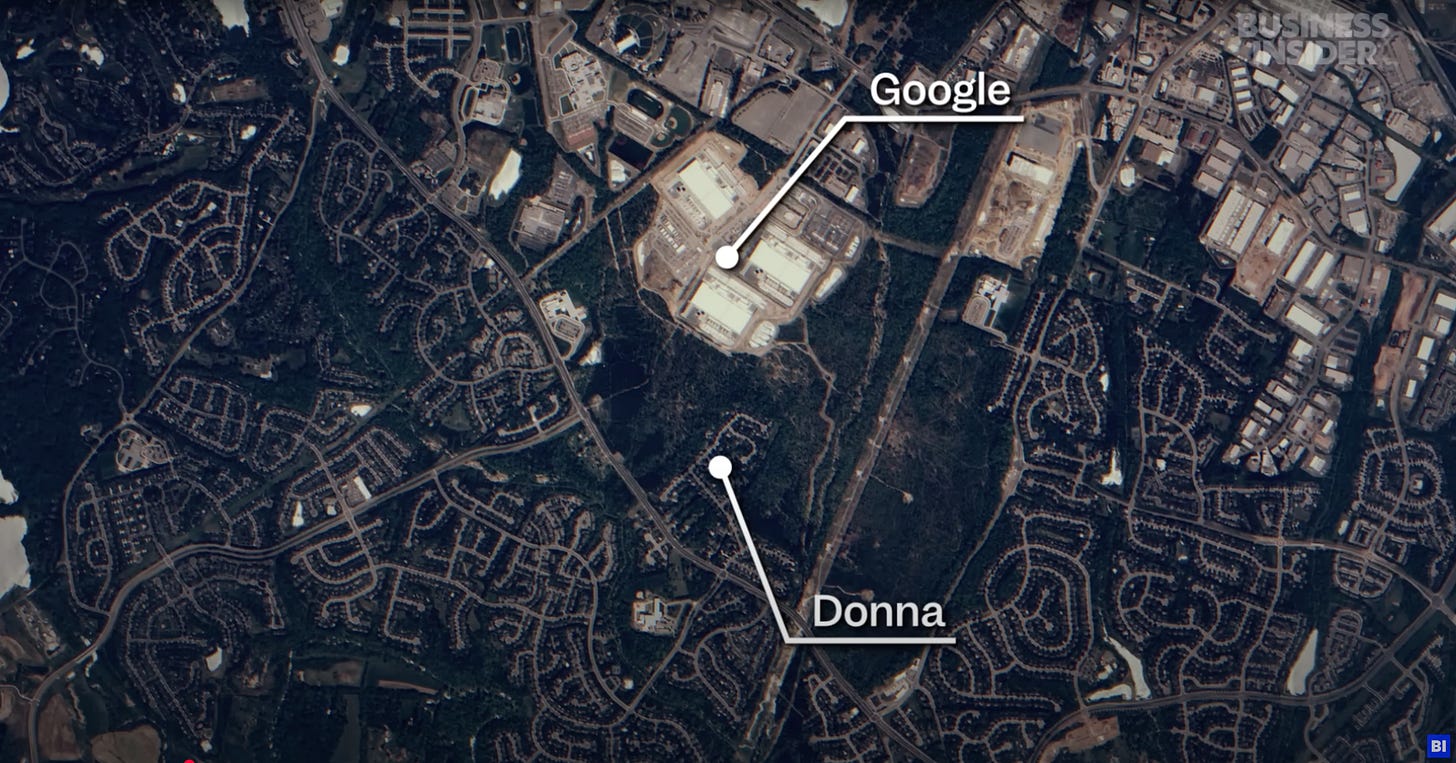

Combined, these capabilities have allowed the tech giants to build data centers at a staggering pace, even when such facilities are deeply unpopular with local communities. Marketed as engines of regional development, data centers in reality provide few permanent jobs, attract little ancillary high-tech industry, and consume vast amounts of water and energy—often at the expense of nearby residents. Unsurprisingly then bottom-up resistance has not been uncommon. Data Center Watch has documented over 140 activists groups across 24 states, but only a half-dozen cases of data center projects have been blocked by local resistance, suggesting how easily local resistance is outmaneuvered by the tech giants.

(This new Business Insider mini-documentary shows how homeowners in Northern Virginia have been powerless to stop the wave of new data center construction happening in their own neighborhood.)

Concluding Thoughts

The Abundance agenda frames America’s crisis as one of excess proceduralism—that endless red tape has made it impossible to build. But the data center boom is evidence of an America that can still build, and at staggering speed, when powerful, well-organized actors are behind it.

Zoning laws, permitting processes, and environmental reviews bend easily for hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, even as they may block projects backed by disorganized/poorly-resourced constituencies such as renters, voters, or subnational agencies. What looks like procedural paralysis is, in fact, a system that privileges powerful actors.

The problem then isn’t that America has lost the capacity to build—it has lost the capacity to build for the public. And until that changes, the country will likely keep getting more data centers instead of affordable homes and high-speed trains.

Democrats have won Loudoun County, Virginia in every presidential election since 2008. In 2024, Kamala Harris won 56% to Donald Trump's 40% in the county.

Hacker, Jacob S., Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen. 2021. “The American Political Economy: A Framework and Agenda for Research.” In The American Political Economy, eds. Jacob S. Hacker, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen. Cambridge University Press, 1–48. doi:10.1017/9781009029841.001

Don't forget state preemption, which has been used for housing and renewables, but increasingly for (fossil) energy and data centers. State-level lobbying (fragmentation point from APE) is arguably more important than the Federal lobbying for dealing with local resistance---just take away permitting or zoning authorities!

woo Irvine CA picture ( my hometown)