The evolution of the cloud computing business model

How the cloud transformed from a basic utility to a platform for innovation

An earlier version of this essay was originally posted to AI Supremacy on May 8, 2025. Thank you Michael Spencer for inviting me to contribute.

Cloud computing is often likened to a basic, fungible utility such as electricity or water. Back in 2014, Matt Wood, former chief data scientist of Amazon’s cloud business, even explicitly said that it was their goal to deliver “computing power as if it was a utility.” And like a utility, the cloud quietly powers much of our digital lives—largely invisible yet completely essential. Just as a power outage can paralyze a city, a cloud outage can bring the digital world to a standstill.

But comparing the cloud to a utility doesn’t feel quite right. The firms that dominate it are nothing like water, gas, or electricity providers. (How many utility companies can you name off the top of your head?) Even telecom giants like AT&T or Verizon, which offer a more sophisticated kind of utility, feel different. Rather than acting like sleepy utility companies, quietly collecting revenue from every customer that touches their cloud, cloud providers are tech companies in the most classic sense—defined not by stability but by relentless disruption.

To be clear, these firms do also offer the most basic, utility-like servers and likely always will. But where they diverge from traditional utility providers is in their relentless push to create new value beyond these foundational services, from AI-powered computing clusters and custom-designed silicon chips to sophisticated software platforms.

In this essay, I trace the evolution of the cloud computing business model—from its early days as a utility-style service focused on providing low-cost, commoditized storage and compute power, to its transformation into a high-margin, value-added platform. These differentiated services, ranging from AI tools to data management platforms, define their competitive advantage and justify their premium pricing.

The cloud-as-utility business model

Before the cloud, running a business in the digital age meant becoming a part-time infrastructure company. Organizations had to build and maintain their own IT backbone—buying physical servers, networking equipment, and storage drives, then installing them in on-site server rooms. Even basic functions like email, file sharing, or internal software systems required significant investment in hardware and a dedicated IT team to keep everything up and running.

For large enterprises, the burden scaled dramatically. Maintaining infrastructure often resembled running a miniature data center, complete with redundant power supplies, cooling systems, 24/7 security, and specialized staff for maintenance and support. And the costs didn’t stop there. To remain competitive, firms had to keep pace with the rapid hardware refresh cycles driven by Moore’s Law, replacing and upgrading systems every few years. This meant physically swapping out servers, migrating data with minimal downtime, and managing increasingly complex software environments—all while trying to avoid disruptions to the business’s day-to-day operations.

Cloud computing entered the corporate mainstream with the promise of alleviating these costs. Rather than owning and maintaining their own hardware, businesses could now rent their IT infrastructure. No more server rooms, no more costly upgrade cycles. Cloud providers handled the physical hardware, maintenance, and updates behind the scenes, allowing companies to stay current with the latest technologies without the usual costs and complications.

Where businesses once needed to make large investments in servers and infrastructure, even buying more capacity than needed to account for future growth, the cloud allowed businesses to rent exactly the computing power they needed, when they needed it. This pay-as-you-go model turned IT infrastructure from a fixed capital expense into a flexible operating cost, dramatically lowering the barrier to entry. For many businesses, this created new kind of agility—scaling resources up or down with a few clicks instead of months of planning and procurement.

What makes cloud computing more cost-effective is its ability to operate at scale. Its no surprise that cloud providers benefit from basic economies of scale. The large fixed costs of running a data center—such as land, cooling systems, security personnel—can be spread across more infrastructure, which lowers the per unit cost of computing. But scale also unlocks another, more powerful advantage: higher utilization rates. In the traditional model, companies had to build out enough infrastructure to handle peak demand, even if that demand only occurred a few times a year. And as a result, servers sat idle most of the time. By pooling demand across many customers with different usage patterns, cloud providers can smooth out spikes and troughs, keeping the shared infrastructure running closer to full capacity at all times. The result is higher efficiency (and lower costs) that get passed on to customers.

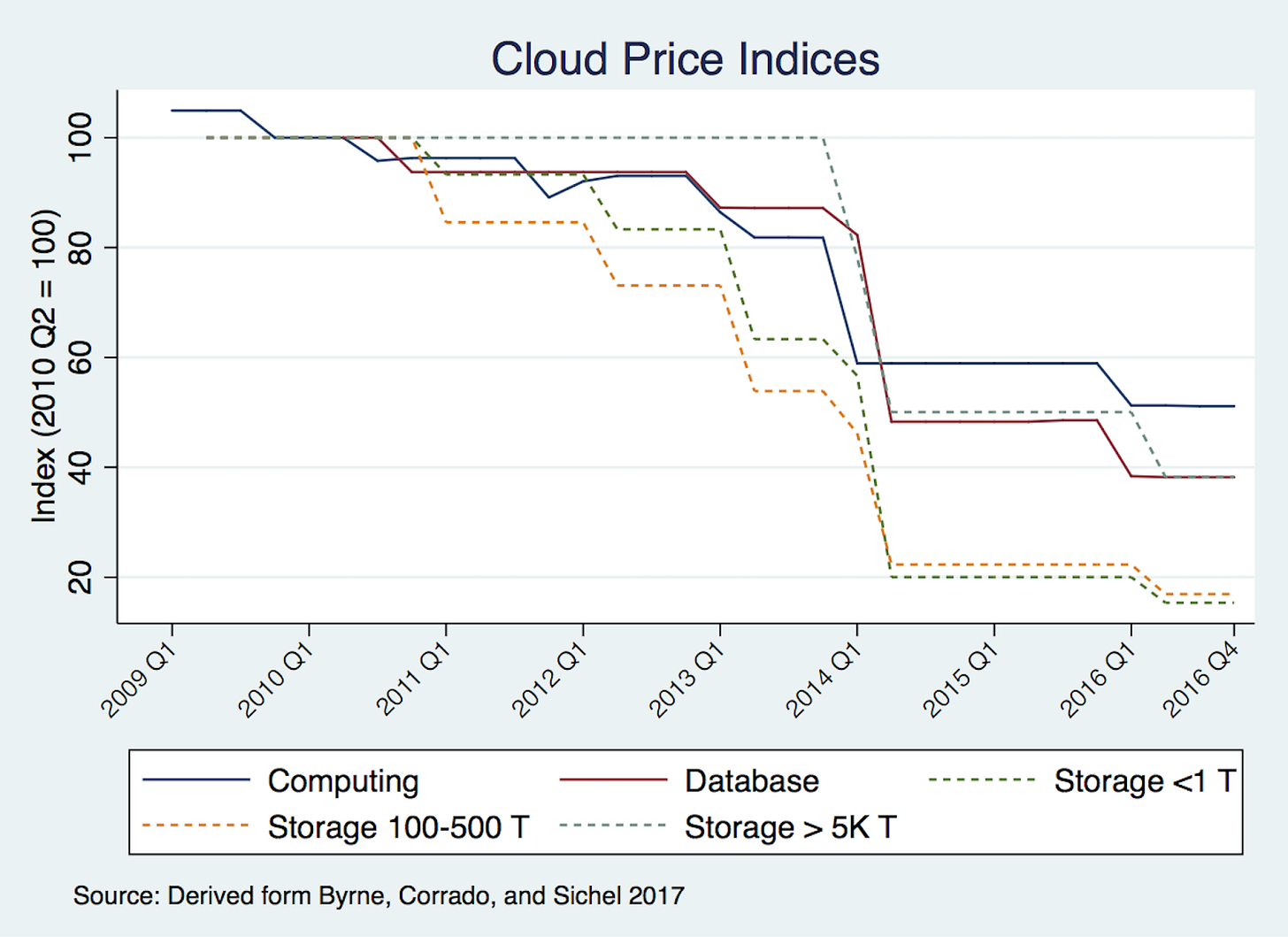

Cost savings was the cloud’s primary selling point. Unsurprisingly, then, providers competed aggressively on price, focusing on offering the lowest rates for the most basic, commoditized server resources. The cheaper the compute, the more competitive it became in the marketplace. Eventually, this competition led to a price war in the early years of cloud computing, where any price cut announced by one vendor was quickly matched, if not undercut, by another within days. According to Data Center Knowledge, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google made 25 price cuts on basic cloud resources like compute and storage between early 2012 and March 2013. This trend accelerated in 2014, with price reductions becoming both larger and more frequent. CRN, an IT trade publication, reports:

Google cut pricing for its Compute Engine Infrastructure-as-a-Service by 32 percent and storage by 68 percent for most users. A day later, AWS (Amazon’s cloud) slashed pricing for its cloud servers by up to 40 percent and cloud storage by up to 65 percent. A few days after that, Microsoft said it's introducing a new entry-level cloud server offering that will be up to 27 percent cheaper than its current lowest service tier.

In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Byrne et al. (2017) conducted a systematic analysis of compute and storage prices among the top cloud providers, finding that between 2009 and the end of 2016, cloud processing costs dropped by approximately 50%, while storage prices declined by 70–80% over the same period.

In many ways, this race to the bottom mirrored the logic of the Silicon Valley playbook: aggressively subsidize costs to capture market share, then rely on scale and network effects to create market dominance. The strategy sacrificed short-term profits to achieve long-term control. And by driving prices down, cloud providers could expand their market share, knowing that once customers came on board, they were likely to stay due to high switching costs. After a business migrates to a specific cloud platform, moving to another provider is a costly and complex process.

During this time, cloud providers focused on filling data centers with off-the-shelf, commodity hardware and prioritizing universal compatibility such that any software could run on any hardware. The focus on was creating interfaces between each layer of the stack such that suppliers could plug-and-play at any level of the stack. In this way, cloud firms also resembled the classic asset-light Silicon Valley firm—leasing or contracting out whatever they could lower in the supply chain.

This approach is not unfamiliar to the cloud giants. All three had previously found tremendous success using this very strategy—monopolizing markets by temporarily slashing costs or even offering services for free—in their previous businesses. Google did it with search, Amazon with online retail, and Microsoft with its productivity software and operating system. And so, armed with billions in cash and a playbook that had worked before, the cloud giants dove headfirst into a tit-for-tat price war, aggressively cutting costs throughout the early to mid-2010s.

In some ways, a price war is a natural part of the industry’s maturation process. For the cloud sector, it lowered the barrier to entry, encouraging businesses that might have been hesitant to shift their IT infrastructure to the cloud. For providers, however, it was an expensive gamble—an aggressive attempt to gain market share.

Admittedly, evaluating the efficacy of price cuts on increasing the market share of any individual vendor is much more complicated than can be assessed here. However, from looking at overall shifts in marketshare in the 2010s, it would appear that this strategy didn’t play out quite as planned. Amazon, which was the most aggressive in its price cuts, held its market share steady at just over 30 percent for most of the decade. Microsoft, on the other hand, saw a consistent rise during the same period. Meanwhile, smaller cloud vendors such as Dimension Data, Joyent, and GoGrid were priced out of the industry—so in that sense, the strategy had some success. But when it came to dramatically reshaping the competitive landscape among the top players, the results were far less impactful.

One reason for this is that, by the mid-2010s, customers started to take a multi-cloud approach rather than relying solely on a single vendor for all their IT needs. This approach helped companies avoid vendor lock-in, giving them greater flexibility and bargaining power. Another reason was that some companies had built-in path-dependent advantages. For instance, Microsoft was able to leverage its long-standing enterprise connections from its Windows Server business, making it a natural choice for many corporations already embedded in its ecosystem.

But the core issue was that, unlike classic digital platforms, cloud computing doesn’t benefit from strong network effects. Platforms like Amazon.com or Google Search become more valuable as more people rely on it, creating a self-reinforcing loop that drives growth. As a result, Amazon and Google has monopoly shares in their respective e-commerce and search markets. In contrast, the inherent value of a cloud provider isn’t directly tied to how many customers it has, besides the fact that scale translates to cheaper costs.

By the late 2010s, the cloud providers—at least those still in the game—seemed to recognize that price competition alone wasn’t sustainable. Even though the top players were flush with cash, none of them were truly profitable under the existing model. AWS, the market leader, didn’t turn a profit until 2015, nine years after its launch. The cloud needed a new model, and as we shall turn to next, that’s exactly what happened.

The cloud-as-innovation-platform business model

If the cloud, like electricity, is a fungible utility, then the prerogative of the cloud industry would be as straightforward as moving as much of the world's existing IT infrastructure into the cloud. In a way, this isn't a bad business to be in. According to Gartner, global IT spending in 2010 was already at $3.4 trillion—by all means, a very attractive market to disrupt. Here, the cloud’s total addressable market should in theory be equal to global IT spending, or less—since the cloud, with its higher utilization rate, would reduce IT costs thereby stunting global spending. And since the cloud business model is all about taking advantage of scale to increase IT infrastructure efficiency, the growth of the cloud sector should also be pegged to the growth of global IT spending.

This, however, hasn’t been the case. Instead, the global cloud computing market has far outpaced global IT spending growth, surging from about $24.63 billion to $156.4 billion between 2010 and 2020—a 635 percent total increase or an annualized increase of roughly 20.3 percent. By contrast, global IT spending only saw a 2.14 percent annualized increase (to approximately $4.2 trillion in 2020) over the same time period.

This tenfold difference is obviously due, in part, to the rate at which traditional businesses are converting their IT infrastructure into cloud spending. But the other part of that number is that businesses are moving to the cloud, not to save on IT costs but to enable new revenue-generating activities. In other words, they’re not just looking for cheaper infrastructure—they’re willing to pay a premium for cloud services that create new value.

In a 2016 interview, Microsoft’s top cloud executive Scott Guthrie said that Azure (Microsoft's cloud business) was no longer competing with Amazon on price but was instead “competing more in value.” And by “value,” Guthrie was referring to “the higher-level services, the features, the performance, and the ability to differentiate or deliver true innovations.” He noted that this marked a shift from “two or three years ago, where I think it was more about cost per VM (virtual machine) or cost per storage.” Indeed, around the mid-2010s, the cloud price wars largely subsided.

Whereas the cloud-as-utility business model emphasized interoperability between software and hardware, this flexibility-first paradigm started to hit its limits as the industry started to move into higher value added workloads. Performance bottlenecks, latency issues, or sheer limitations in hardware performance pushed cloud firms to pay closer attention to the underlying hardware. And in response, cloud providers are vertically re-integrating, moving away from hardware-agnosticism and back to embracing full-stack control. Today, a key aspect of each cloud’s competitive advantage lies how its has recoupled software and hardware—developing specialized infrastructure tailored for specific workloads.

Concretely, what do these differentiated, higher-level services look like? Let's walk through a few examples.

Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) + Software-as-a-Service (SaaS)

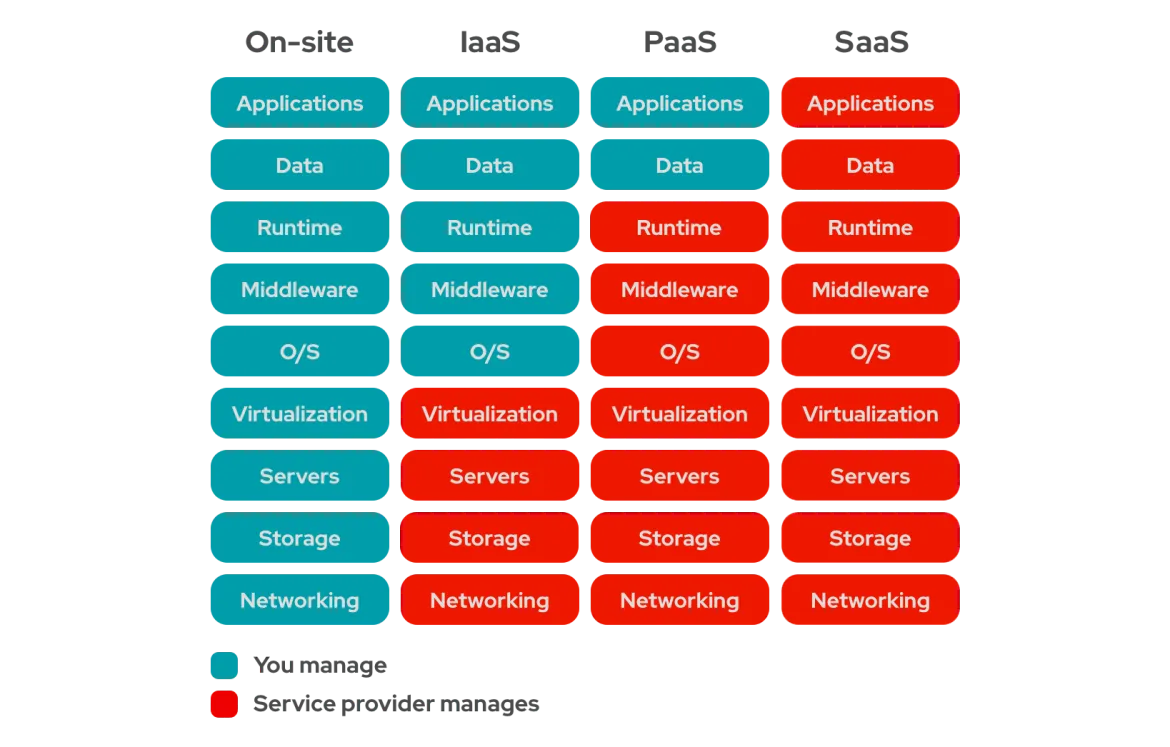

Traditionally, when there’s talk about providing higher-value services in the cloud industry, people are usually referring to platform-as-a-service (PaaS) or software-as-a-service (SaaS)—and that’s in contrast to infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS), or what I’ve been calling the cloud-as-utility business model. Simply put, PaaS and SaaS are built on top of the three basic components of IT infrastructure (compute, storage, and networking). And because each PaaS and SaaS provide additional value on top of the bare infrastructure, they are priced at a higher rate than the underlying compute, storage, and networking they consume.

The easiest way to understand the differences between IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS is to think of running a restaurant. IaaS is like leasing a restaurant space and equipping it with everything you need to start cooking—ovens, stoves, refrigerators, tables, and chairs. You’re still responsible for hiring staff, designing the menu, and managing the kitchen. It gives you the raw infrastructure, but you handle most of the operations. PaaS is like walking into a fully equipped and staffed kitchen where everything is set up for cooking. You don’t need to worry about maintaining the equipment or hiring dishwashers—your job is just to focus on creating new dishes and running the menu. SaaS is like going to a restaurant, reading the menu, and ordering your meal. Everything is ready-made for you. You don’t worry about the kitchen, the staff, or the ingredients—you just enjoy the finished product.

Each of these services also caters to a different audience. Whereas IaaS is primarily designed IT operators, PaaS is built for software developers. It handles the behind-the-scenes infrastructure—like provisioning servers, connecting them to storage, and implementing security protocols—so developers can focus on writing code and deploying applications without getting bogged down by system administration. Meanwhile, SaaS is aimed at end-users, who interact directly with the finished software product through a web or desktop application. Whether it’s sending an email, managing sales leads, or editing a document, SaaS users engage with the software itself, not the underlying code or infrastructure.

Microsoft, Google, and Amazon operate in all three layers at varying capacity. All have robust IaaS and PaaS offerings. And among the three, Microsoft also has notable SaaS services, such as its Office 365 suite. But given the modularity of the cloud stack, other firms can nevertheless plug in at the PaaS or SaaS layer and build on top of the infrastructure that is provided by these three firms. For instance, Salesforce, a large SaaS provider, runs on Amazon’s cloud platform.

Advanced hardware

If PaaS+SaaS is about adding value at the top of the cloud stack, another way cloud providers offer higher-value, differentiated services is by enhancing the bottom of the stack. One way to do this is by investing in specialized hardware—servers that are difficult for traditional IT departments to purchase, deploy, or manage on their own due to the complexity, cost, and expertise required.

One example of this is the specialized hardware required for AI clusters. Building an AI cluster isn’t as simple as stacking a few high-powered servers together; it involves assembling a highly complex, technically sophisticated system designed to handle massive parallel processing workloads. These clusters rely on specialized components like high-end GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) and ultra-fast networking technologies (e.g., InfiniBand technology) to ensure seamless data transfer between processors.

Configuring advanced hardware can require deep expertise in data centers, which cloud providers have invested heavily in over the years. They have highly trained staff and R&D teams dedicated to improving data center uptime, energy efficiency, and cooling technologies. For most businesses, doing all this in-house would be cost-prohibitive and operationally overwhelming.

Infinite capacity

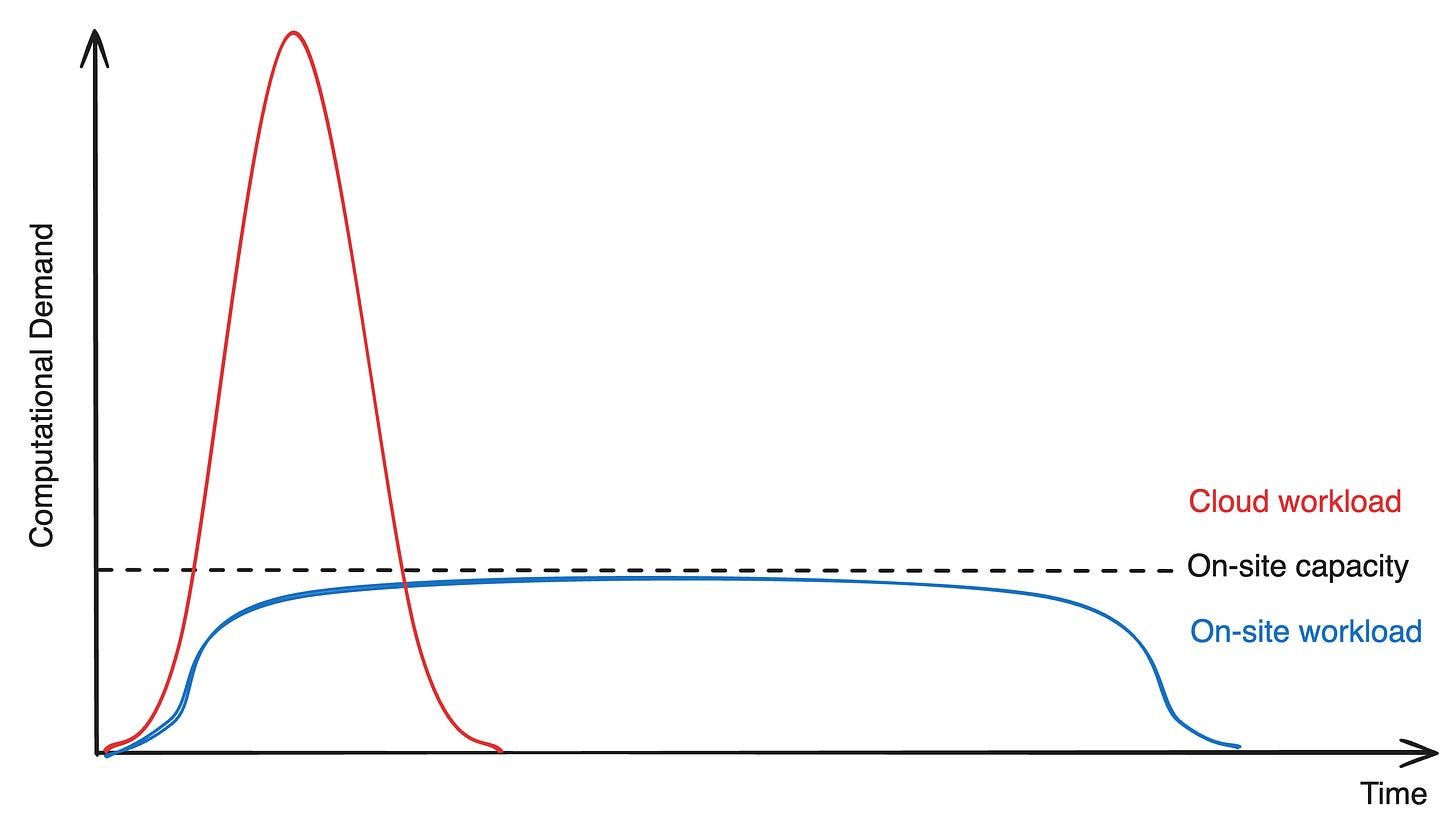

The cloud also enables businesses to operate as if computational limits don’t exist. Since cloud resources can be scaled up or down on demand, companies can offload their computationally expensive workloads into the cloud whenever their on-site infrastructure falls short.

Imagine a team of researchers at a biotech firm needs to run a protein folding simulation—a task that’s notoriously computationally intensive. (You could easily swap this out for a team of AI researchers training a new AI model.) Their on-site servers—represented by the dotted line in diagram—are sufficient for handling day-to-day operations, but running these protein folding simulations on that infrastructure would take an impractically long time (as represented by the blue line).

Rather than investing in additional hardware just to speed up one-off simulation projects, the biotech firm can offload the extra workload to the cloud, renting as many resources as they need to get the simulation done in a timely manner (represented by the red line). This not only accelerates research timelines but also empowers businesses to take on more ambitious, resource-intensive projects without being constrained by their existing infrastructure.

Concluding thoughts

This isn't an exhaustive list of the ways in which cloud providers are transitioning to higher-value, differentiated services. But these examples should begin to give us a sense of why cloud spending is far outpacing IT spending.

In the cloud-as-utility model, the cloud’s growth was a function of the growth of traditional IT. When businesses expand their IT needs—whether that's increasing the amount of data storage or the number of employees who need access to basic enterprise software—the demand for cloud infrastructure grows in parallel. Under this model, the cloud didn’t enable fundamentally different types of business activities, but was simply a utility that offered a more efficient way to power existing operations.

By contrast, the cloud-as-innovation platform model flips this on its head. Instead of merely being a byproduct of traditional IT expansion, the cloud itself becomes the driver of new business activities and technological breakthroughs. In this model, the cloud isn’t just a more efficient way to run existing software—it’s the foundation that enables entirely new capabilities that wouldn’t be possible in the traditional infrastructure model. In other words, the cloud has transformed from a traditional cost center to a powerful source of competitive advantage and a force multiplier for innovation.

As should be clear by now, AI is one of the biggest examples of the kind of value-added service that the cloud-as-innovation platform business model has enabled. Unlike traditional IT workloads, AI requires vast computational resources, specialized hardware, and sophisticated software frameworks—resources that most businesses simply cannot build or maintain on their own.

Had the cloud remained a pure utility—focused only on providing basic, fungible infrastructure—we might not have the AI capabilities we see today. Training today’s generative AI models requires thousands of high-performance GPUs running in parallel, supported by complex data pipelines and finely tuned algorithms. These capabilities didn’t emerge overnight. They were gradually developed and made accessible, in large part, through the evolution of the cloud business model.

Yet since the release of ChatGPT, the cloud has often been portrayed as nothing more than an appendage to the generative AI boom. Discussions about its role have largely centered on AI training, inference workloads, and the computing power required to sustain large-scale models. What’s often overlooked, however, is that many of these trends began long before generative AI took center stage.

This brief history of the cloud’s evolution should remind us that (1) the cloud existed long before the AI boom, and (2) it serves as a platform for a vast range of innovations beyond AI. From scientists using it for protein folding research to advance drug discovery, to quants running complex financial simulations, to climate scientists modeling weather patterns, the cloud-as-innovation platform model has empowered industries across a wide range of fields with faster experimentation, deeper analysis, and more sophisticated simulations.

The AI boom has pigeonholed the cloud and its vast infrastructure as nothing more than the platform on which AI is trained and deployed, creating a kind of myopia over the breadth of innovation that is possible with today’s technologies. If we continue to see the cloud solely through the lens of AI, we risk overlooking its broader potential—and in doing so, limiting our collective imagination for what the future holds.