Rethinking AI diffusion in China

Enterprise software and cloud adoption have a key role in AI diffusion.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that China is now competing head-to-head with the United States at the frontier of large language model (LLM) development. Models like DeepSeek’s R1 and V3 have demonstrated capabilities rivaling, and in some cases exceeding, those of leading U.S. models. Meanwhile, Alibaba’s Qwen3 has climbed to the top of global benchmarks in reasoning and language tasks. These achievements are all the more notable given the constraints Chinese firms face under U.S. export controls, which limit access to state-of-the-art Nvidia hardware.

By some measures, China is no longer playing catch-up in AI model development—it is already there. But reaching the technological frontier is only part of the story. As Jeff Ding has argued, what really matters for long-term economic advantage is diffusion: how widely and effectively these innovations are adopted across the broader economy.

This post weighs in on the ongoing debate around AI diffusion in China. Broadly speaking, I've encountered two contrasting views. On one side is the more common view which argues that China is well positioned to harness the benefits of AI and, as with other critical technologies, will eventually surpass the United States in both adoption and impact.

On the other side is Jeffrey Ding, who argues that China faces a diffusion deficit—that is, a gap between cutting-edge AI development and its widespread adoption across the economy. And because diffusion, at least in Ding's analysis, is key for economic prowess, China's AI diffusion deficit means that we're overestimating the economic impact that AI will have in China.

From there, I'll add my own position—that China does have a diffusion deficit but for reasons quite different from what Ding has argued.

The diffusion advantage argument

Most accounts fall into the camp of seeing China as having an edge in the diffusion of AI—and perhaps unsurprisingly. After all, the country does have a strong track record for rapidly diffusing critical technologies. Mobile payments, for example, reached mass adoption far more quickly than in the U.S.—by 2019, 35% of Chinese consumers were using mobile payments compared to just 8.8% in the U.S. High-speed rail is another example with the state pushing for its adoption and building some 30,000 miles of rail since Xi took China's top position in 2013.

The most recent and arguably most salient example is EVs with China going from a marginal player to the global leader in EV production and adoption in the span of several years. Thanks to a combination of state subsidies, local government incentives, infrastructure build-out, and industrial policy targeting both supply and demand, China accounts for two-thirds of global EV sales as of 2024. These examples suggests that China can diffuse new technologies throughout its economy at quite a remarkable speed, and the idea is that the same capacity for diffusion will be applied to AI.

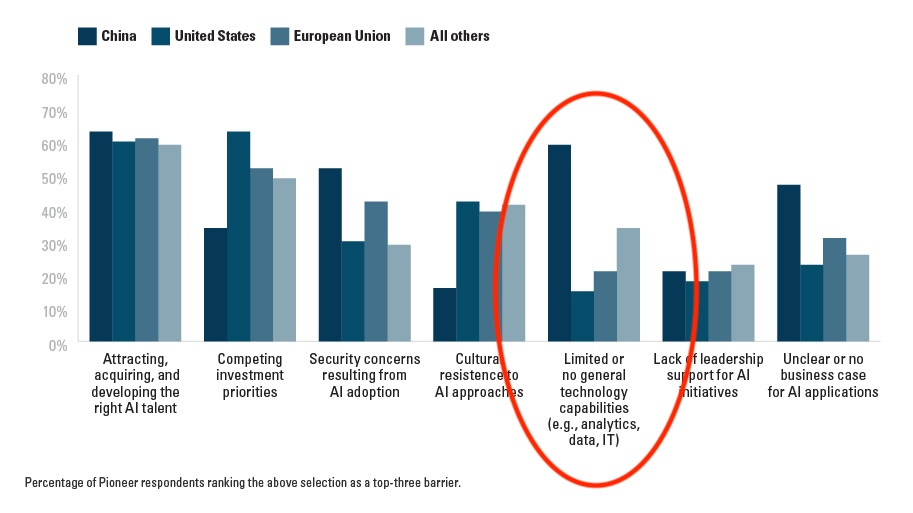

As Kaiser Kuo has argued, part of the reason China has an edge in the diffusion of AI is cultural. Chinese society, he suggests, tends to have "a techno-optimistic orientation where innovation is associated with improved material well-being, state capacity and national rejuvenation." By contrast, the U.S. has what he calls a more "Black Mirror" mindset: a cultural tendency to view new technologies, especially AI, with suspicion or dystopian anxiety. As a result, U.S. domestic demand may be more restrained. Indeed, the field of AI ethics and the concerns it raises about the unrestrained pursuit of AGI is virtually nonexistent in China, meaning the country are free of the speed bumps that would normally slow the rollout of AI in the West.

Beyond cultural factors, Kuo has also pointed to the structural advantages of China’s tightly coordinated innovation ecosystem—specifically, the close alignment between public institutions, academic research, and private firms. He cites examples like Zhipu AI, which emerged directly from a university lab and was funded by state-affiliated venture capital, as evidence of this state-academia-industry nexus in action.

What he’s describing reflects a broader pattern across many of China’s high-tech sectors: first, the state provides patient capital to support long-term, high-risk projects that would struggle to survive under the short-term pressures of profit-driven private investment; then, rather than sheltering these ventures, it exposes them to intense domestic competition such that market pressures impose discipline and drive up performance. The result is a system where firms, pushed by fierce competition, bring down costs and scale rapidly—accelerating the mass diffusion of technological breakthroughs, as seen in China’s electric vehicle and solar manufacturing sectors.

The diffusion deficit argument

The "China is good at technology diffusion" is certainly convincing, but if we look carefully at the types of technologies that have successfully diffused, we can see that they largely fall into two categories—consumer-facing tech or large-scale infrastructure. Mobile payments, EVs, and AI apps like DeepSeek or Yuanbao installed on smartphones are all examples of consumer technology. These tend to diffuse quickly because the barriers to adoption are low. More importantly though, their spread doesn’t necessarily translate into substantial productivity gains across the broader economy. On the other hand, infrastructure projects like high-speed rail succeed not because of organic market uptake, but because the state can orchestrate their rollout from the top down and absorb short-term losses if these ventures aren't immediately profitable.

These two types of technologies differ quite a bit from the type of technology that characterizes AI—or what Jeffrey Ding, among others, would call a general purpose technology (GPT). Unlike infrastructure-based technologies, the diffusion of a GPT can’t be mandated from the top because adoption depends on market viability and firm-level incentives. And unlike consumer tech, its transformative potential doesn’t come from widespread consumer adoption, but from its capacity to enhance productivity across a broad range of industries. What truly matters in the diffusion of AI, then, isn’t how many people are chatting with DeepSeek, but how many firms are embedding AI into their business processes, reshaping workflows, and leveraging it to gain a competitive edge.

Indeed, AI diffusion in China may not be has robust as it first appears. This, in fact, is one of the core argument Ding makes in a recent article. While China has clearly produced a number of frontier innovations—evidenced by the growing roster of cutting-edge, homegrown LLMs—the more critical, and often overlooked, factor in translating technological breakthroughs into economic power is diffusion. And on that front, Ding argues, China is behind.

Technology diffusion is tricky to measure and any attempt to do so is requires creativity. In Ding’s case, he counted the number of universities in each country that have placed at least one research paper at one of leading AI conferences. This, he argues, is a good proxy for understanding the geographic diffusion of AI because it represents how widely AI expertise is distributed. His findings was that China had 29 such universities; the U.S. had 159. This gap suggests that beyond China’s elite universities and tier one cities, the country lacks the institutional depth needed to support widespread AI diffusion such as the kind of skilled AI engineers who can integrate and deploy this general-purpose technology across diverse sectors of the economy.

To explain China’s weak AI diffusion—and the U.S.’s relative strength—Ding zeroes in on the role of education and training institutions in expanding the talent pipeline. Skills/education are key because AI is highly technical and requires sophisticated engineering know-how in firms that are adopting AI (e.g., knowing how to monitor the system, how to update the system, how to benchmark between models, and how to integrate these models into existing workflows, etc). And so, it’s not just about producing elite researchers at top universities or firms, but about cultivating a broad base of engineers across regions who can work with, adapt, and implement AI technologies throughout the economy.

You have to walk before you can run

Ding is a political scientist, and his argument, in classic political science fashion, is essentially an institutional one: China’s AI diffusion weakness lies in its lack of a broad base of training and skills institutions beyond the handful of elite ones in top tier cities. And without this broad foundation, China’s ability to diffuse AI widely—and to translate frontier innovation into economy-wide productivity gains—is fundamentally constrained.

I’m quite sympathetic to Ding’s argument and agree that China does—and likely will continue to—lag behind the U.S. when it comes to AI diffusion. But if what we care about is whether firms across sectors and across China's geography can adopt AI for productivity-enhancing purposes, then skill institutions are really just a small part of the explanation.

As I see it, what matters more is the level of digitization across China’s economy—which, compared to the U.S., still lags significantly behind. The intuition is simple: for firms to adopt AI, they must have basic IT practices in place e.g., storing data in a structured format, ability to process large quantities of data, etc. Without these basic IT capabilities, adopting AI would be like learning to run before knowing how to walk.

[Updated July 22nd, 8pm: Several readers have mentioned that Jeffrey Ding does talk about IT spending lagging in China as a cause for slow adoption of AI in China. That’s my mistake for overlooking this point.]

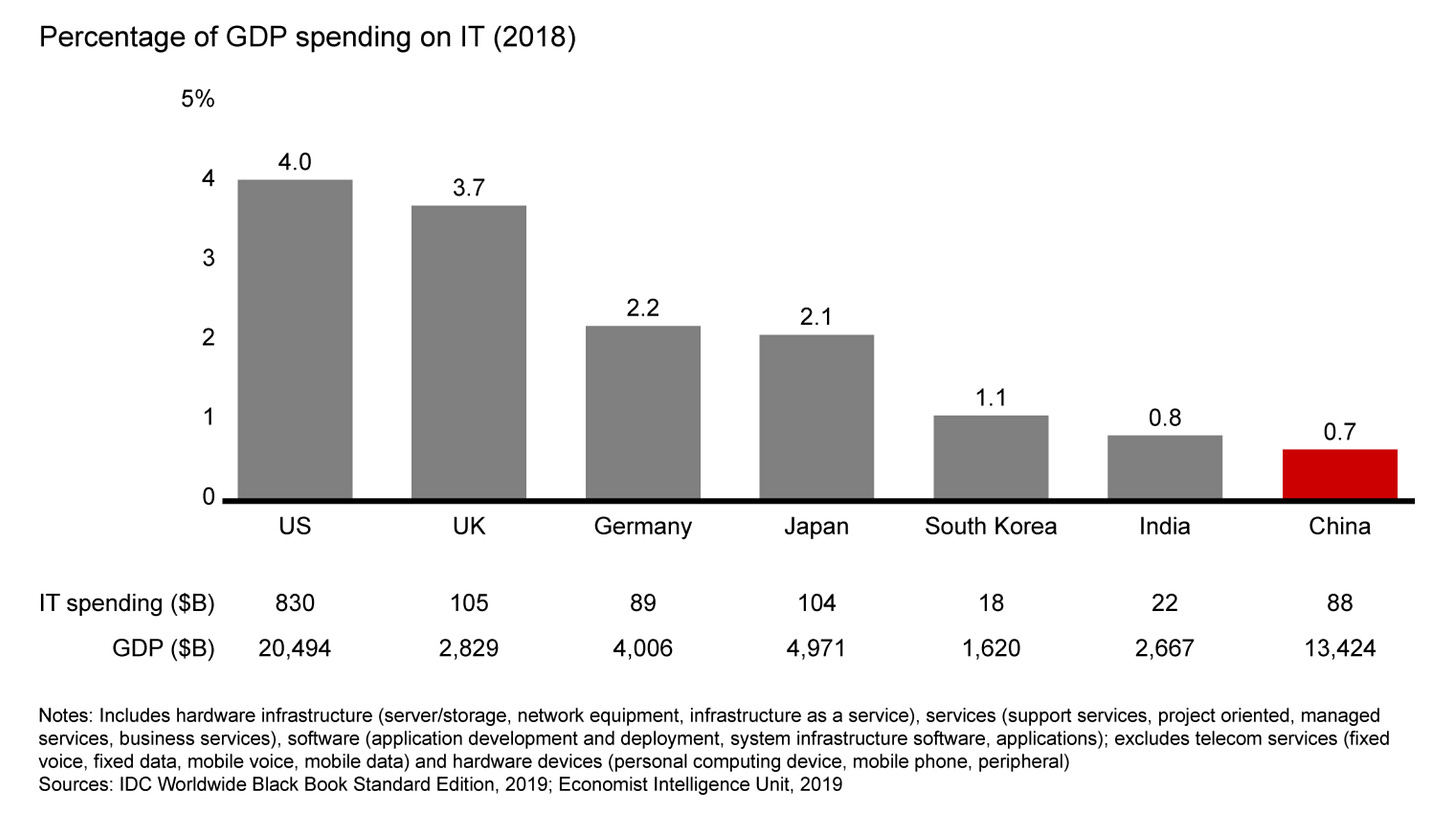

To assess how far along China is in terms of digitization, we can turn to several proxy indicators—but perhaps the clearest is IT spending, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP. As the chart below shows, China ranks lowest among this group of seven advanced economies in IT spending relative to GDP. Even in absolute terms, China spends just one-tenth of what the U.S. does, trailing not only the U.S. but also Germany, the U.K., and Japan. On top of that, Chinese firms devote less of their IT spending toward software services (as opposed to hardware/infrastructure) compared with those in other large economies. Combined, this suggests that China’s digital foundation remains comparatively underdeveloped.

Spending on IT/digitization is one issue—the weakness of China’s tech sector when it comes to delivering IT infrastructure and services is another. As I’ve argued in previous posts, China’s cloud computing sector significantly trails that of the U.S. The more robust the cloud is, the easier it is to adopt AI solutions because it lowers the barriers to entry: firms don’t need to invest heavily in their own computing infrastructure (which is both capital and human-capital intensive) to access AI tools. The gap is even more pronounced in enterprise software (or SaaS), where China lacks the kind of mature, integrated ecosystem found in the U.S. (as of 2024, the U.S. had over 9,000 SaaS companies; China only had 443).

These limitations—namely, low levels of digitization on the demand side and an underdeveloped supply of digital infrastructure (cloud computing and enterprise software)—pose serious constraints on the broader diffusion of AI. In this sense, the challenge runs even deeper than what Ding suggests. It’s not just a question of skills institutions; it’s also about the availability of patient capital, the structure of labor markets, and the incentives firms face to invest in long-term digital transformation. And there's also the simple fact that digital technology adoption has a certain path-dependency to it: already using digital services makes it easier to adopt new digital services such as AI.

Concluding thoughts

It might be a little odd to argue that China is not digitized in 2025. After all, Chinese users seems to be far more advanced than their western counterparts in e-commerce, food delivery, mobile payments, and essentially living on their phones. But that's because the adoption of digital technologies in China has largely happened in the realm of consumer products. The story is quite a bit different when we look at how firms are bringing digitization into their business processes. With the exception of the tech sector (and increasingly biotech too), China is still far behind on this dimension.

For AI, this means that in the near term, adoption will likely be driven by China’s sophisticated and fast-moving consumer-facing internet giants, which are already integrating AI into their expansive portfolios of apps and services. As a result, we can expect broad adoption of consumer AI tools. But as I’ve argued, consumer-facing adoption alone doesn’t generate the kind of productivity gains needed to significantly boost the broader economy. The longer-term question is whether China’s SMEs and other non-tech industries will have meaningful AI adoption. The fact that many of firms across the country have yet to adopt even basic digital services makes adopting AI a far greater challenge—after all, you have to walk before you run.

Interesting post. Just had a conversation with a vc who focuses on saas who said they are now seeing lots of demand from PRC businesses because of ai, so things may be changing, and quickly. The spend will be lower per seat/company

Great article! And fysa, chapter 7 of Ding's "Technology and the Rise of Great Powers" does point out that cloud compute adoption and IT spending lags for Chinese firms, relative to US firms (p192-193).